She gazed time and again throughout her short life into the glassy eyes of death in search of salvation but to no avail.

On July 3, 1950, her father, who had been a member of the military wing of the Nazi Party, known as the Waffen-SS, before Germany’s defeat and surrender in 1945 after World War II, was blessed with her. He was a father overshadowed by military strictness and extremely harshness, and his frustration was compounded by witnessing the humiliating collapse of his country and his military future. This led him to alcohol, turning him into a violent and aggressive person, even within his own home.

She looked into his glassy eyes, searching for a father’s affection, hoping to find some sympathy, but to no avail.

Her father’s departure was not unexpected, and afterward, she moved with her mother to live with her stepfather, who subjected her to another chapter of bitter living, no less harsh than that with her father.

She looked into his glassy eyes, searching for a father’s affection, hoping to find some sympathy, but to no avail.

After her mother kicked her out of the house due to constant conflicts, she formed a relationship with a schoolmate. At the age of sixteen, she became pregnant with a child she was unable to keep at such a young age, so she gave her up for adoption.

Then, she became pregnant again with a second child from another relationship at the age of eighteen. And before she gave birth, she was raped in a nightclub, and her tragedy was repeated. However, the child was also given up for adoption.

At the age of twenty-two, she became pregnant again with her third child from her boyfriend, Christian Berthold, who was the manager of the Tibaza Tavern, where she worked as a waitress in the city of Lübeck in the state of Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany.

This time, Marianne Bachmeier decided to keep her daughter Anna, who was born in 1972.

She looked into her eyes and instantly realized that she had become the centre of her life and her remaining hope for love and tenderness.

The child grew up under her mother’s care, who continued working late into the night at the bar. Sometimes, she would take her daughter with her, letting her sleep on a bench in the corner amidst dancers’ laughter and loud music. Other times, the child would wait alone at home after returning from school or stay with a shopkeeper working at a nearby grocery store.

One day, Bachmeier overslept after a late night working at the bar and couldn’t wake up to send her daughter to school, with whom she had argued the previous day. So, Anna went out to play with her friends.

The mother woke up thinking her daughter had gone to school. That afternoon, she went to a photo shoot, having caught the attention of a journalist with her Volkswagen van covered in pictures.

A long time passed without the child returning, causing the mother to become anxious. She quickly contacted the police to report her missing daughter.

The next day, the police knocked on the door to inform the mother that they had found her daughter’s body.

The police arrested the suspect, who turned out to be the 35-year-old neighbor, Klaus Grabowski, who works as a butcher.

During the investigations, it was revealed that Anna couldn’t find her friends with whom she went to play, so she returned home. On the way, she encountered her neighbour Klaus Grabowski, who offered to show her his kittens. After she entered his apartment, he sexually assaulted her, then strangled her with his fiancée’s silk stocking, which she had left in the other room.

When his fiancée returned home, he told her what he had done. An argument ensued, and she immediately left and reported the incident to the police.

While she was outside, he placed Anna’s body in a cardboard box, carried it on his bicycle, and took it to a spot on the banks of a canal, where he buried it in a shallow grave.

When the police arrived at his home, he had already left, but he had left a note for his fiancée, begging her not to abandon him. He said he would be waiting for her at the bar they usually frequented to think about how to get out of this predicament.

Later that night, the police waited for him to arrive at the pub and arrested him.

This was not his first sexual assault. In 1976, he was sentenced to a long period in a psychiatric facility for sexual offenders after being convicted twice of child molestation. However, he was released from prison after agreeing to a legal procedure in which he would be chemically castrated by reducing his testosterone in exchange for his release.

After two years of his release, he went to a urologist and requested hormone treatment to reverse the chemical castration. The court approved this treatment because he reported physical side effects, and he had a fiancée with whom he wanted to start a family. The court assumed he had become an ordinary person who no longer posed a threat to others.

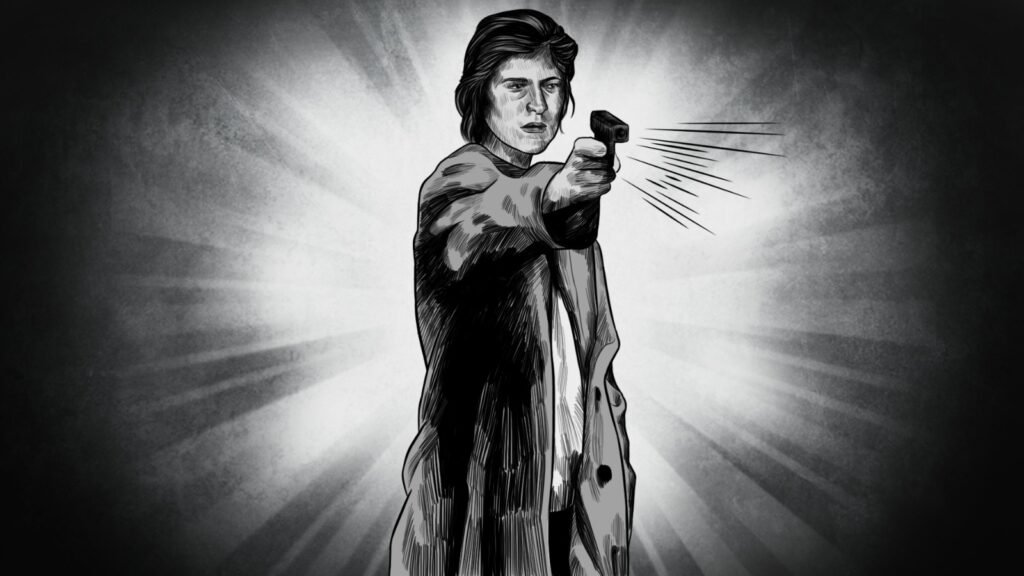

On March 6, 1981, during the third session of the court proceedings, Bachmeier attended the session at around ten in the morning. She entered room 157 wearing her coat, and before the session began, she did not look into the eyes of the murderer this time, deciding to confront justice head-on instead of fleeing as usual.

She raised her hand with a small Beretta pistol hidden in the pocket of her long coat and fired eight shots at the back of the perpetrator, who was sitting three and a half meters away waiting for the session to start. She hit him with seven bullets, killing him instantly.

The police arrested the mother without any resistance after she dropped her gun on the ground and asked the officers holding her, “Is the pig dead?”

The trial of her crime shook the entire German society and attracted significant local and international media coverage. Public opinion was divided between those sympathetic to the grieving mother of a seven-year-old murdered child and those opposed to taking justice into one’s own hands and killing outside the law.

Bachmeier looked into the eyes of the photographers in the courtroom, searching for understanding or appreciation, but to no avail.

She faced their lenses with confidence, like a fashion model, showing no signs of regret or shame.

She sold the rights to her story to the German newspaper Stern for 250,000 marks to cover her defence expenses, and the newspaper published her story in a detailed news series that attracted many readers.

Additionally, a group of sympathizers formed an association called “Exonerate Marianne Bachmeier,” raising 100,000 marks for her, and she received bouquets and support cards in prison.

Bachmeier looked into the judge’s eyes in search of justice, hoping to find vindication, but to no avail.

During her trial, she insisted that she had not planned to kill the man in the courtroom, that she had acquired the gun out of fear and insecurity after her daughter’s murder, and that her shooting him was a moment of emotional outburst after seeing him and some investigation photos of her daughter’s tied body after it was recovered.

This was the defence strategy her lawyer used to avoid a life sentence. The German Criminal Code had abolished the death penalty in 1949. Still, Article 211 stipulates that “the punishment for murder is life imprisonment,” defining a murderer as someone who “takes the life of another person out of a desire to kill, to satisfy a sexual urge, out of greed, or due to other base motives, with malice, cruelty, or dangerous means to others, or to commit or conceal another crime.”

In late 1982, the prosecution charged her with premeditated murder but later dropped the charge. Four months after the proceedings began, in 1983, the court convicted her of manslaughter and illegal possession of a firearm, sentencing her to six years in prison.

The judge adopted this lenient sentence because he was convinced that the killing was impulsive and resulted from the shock of facing the accused, who had confessed to killing her daughter during the trial sessions. A witness claimed that a file containing pictures of Anna’s body was present in the courtroom, and her mother saw it shortly before she shot Grabowski. This was enough reason for the judge to view the crime as unintentional manslaughter.

A year after her sentencing, two German films about her were released in 1984: “Anna’s Mother” and “No Time for Tears: The Bachmeier Case.”

Bachmeier was released after serving three years in prison in 1985. That same year, she married a teacher and, three years later, moved with him to Nigeria, where he had an opportunity to teach German. However, their marriage did not last more than five years, and they divorced in 1990.

Afterwards, she travelled to Sicily to work in Palermo at a hospital that performed euthanasia for terminally ill patients. During her time working at this hospital, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and returned to Germany.

After working for a period at this hospital, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and returned to Germany.

Bachmeier conducted numerous television interviews and collaborated with German director Lukas Bumar to accompany her in her final days to make a documentary about her story. She affirmed that she never regretted her actions, stating she killed Grabowski to prevent him from tarnishing her daughter’s reputation by claiming she had threatened to expose him unless he gave her money and to stop his potential future crimes.

In the documentary “Revenge of Marianne Bachmeier,” produced in 2005, a close friend revealed that Bachmeier had been practising shooting before the incident in an isolated basement under the pub where she worked. However, Bachmeier never admitted to premeditated murder.

On October 17, 1996, as her health deteriorated, Bachmeier breathed her last at the age of 46 and was buried next to her daughter Anna, 16 years after her murder.

The documentary she desired, “The Slow Death of Marianne Bachmeier,” was released in the same year as her death.