On that day in 1981, I was a 12-year-old boy, sitting in front of the TV watching the military parade and listening to the commentator’s passionate speech on the occasion of the eighth anniversary of the October 6th War between Egypt and Syria on one side, and Israel on the other.

During a scene of Mirage jets soaring into the sky, releasing massive amounts of brightly coloured smoke from their jet engines, the camera suddenly tilted sharply toward the ground, and the broadcast cut off. No one understood what had happened, and people remained in a state of anticipation, which over the hours turned into anxiety, further intensified by the continuous patriotic songs, especially when uninterrupted recitations of the Quran followed them.

By the end of the day, the announcer put an end to the uncertainty, officially declaring the death of President Mohamed Anwar Sadat in an assassination.

I wasn’t shocked; I felt like I was watching a movie unrelated to reality. The next day, I went with my mother to my grandmother’s house, and the streets were empty, in unprecedented calm, as if the people had voluntarily imposed a curfew.

A few years before this event, when I was in the fourth or maybe fifth grade, I wrote an essay about the Camp David peace treaty between Egypt and Israel during a writing class. I expressed my astonishment when Sadat stepped out of the Egyptian plane on the grounds of Ben Gurion Airport, with Israeli flags bearing the blue star fluttering in the background. I wrote what I still remember: “The president went to Israel in the ‘infertility’ of their home.” My Arabic teacher smiled, impressed by my writing, and said, “Well done, Ahmad, but it’s ‘in the heart of their home,’ not ‘infertility.'”

In his last speech on September 5, 1981, Sadat addressed the People’s Assembly, explaining the reasons for the sudden arrest of several religious and political figures in what became known as the September arrests.

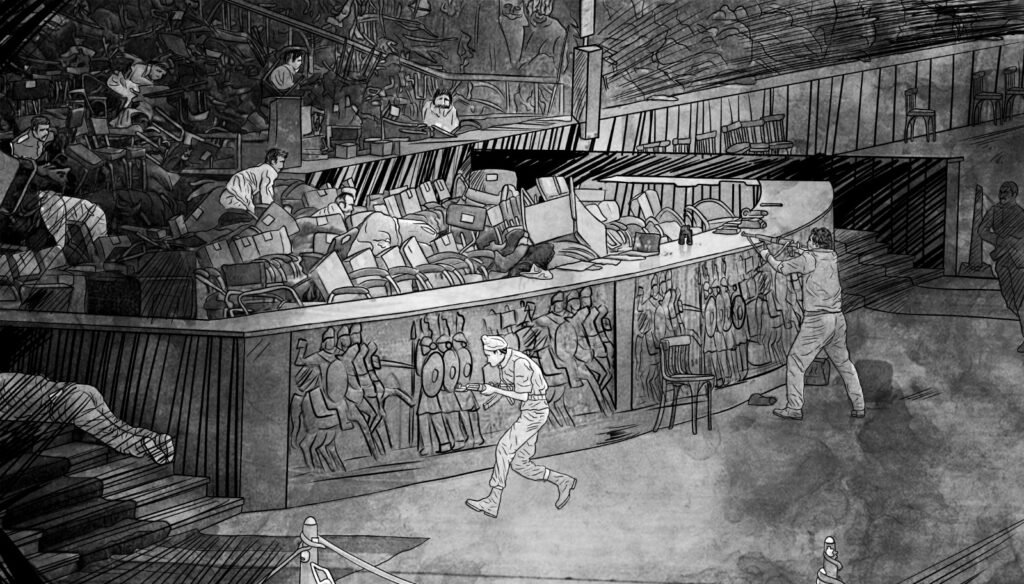

Just one month after this speech, on October 6, the platform incident occurred, where several Egyptian military officers assassinated the country’s president during his attendance at the anniversary of the October War, in which Egypt and Syria launched a major military attack on Israel in 1973 to reclaim their occupied territories.

Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, in his book Autumn of Fury, states that Lieutenant Khaled El-Islambouli—one of the military officers involved in the assassination of Sadat, who was 24 years old at the time of the operation—mentioned three specific reasons during his interrogation in response to one question: “Why did you decide to assassinate President Sadat?”

The first reason was that the laws governing the country did not align with the teachings and principles of Islam, and as a result, Muslims were suffering from all kinds of hardships. The second reason was that Sadat made peace with the Jews. The third reason was the arrest, persecution, and humiliation of Muslim scholars.

Psychological Aspects

Among the psychological aspects that many may not know is that, as Heikal mentioned, El-Islambouli went to his sister’s house for the last time before carrying out the assassination. He wrote a letter and placed it in an envelope, hiding it in her bedroom. His sister did not find the letter until after Sadat’s assassination and the arrest of her brother, who was accused of the assassination.

In the letter, El-Islambouli wrote: “Please forgive me. I have not committed a crime. I want nothing for myself and do not seek promotion or reward. If any harm comes to you because of me, I ask for your forgiveness.” Later, when El-Islambouli’s aunt visited him in prison, she asked him if he had thought about what might happen to his father, mother, and the rest of his family because of what he did. His response was that he only thought about God.

On the other hand, Sadat was pleased with his achievements in the 1973 war, followed by the peace treaty and economic openness. According to Heikal, on September 23rd—just two weeks before his assassination—Sadat gave an interview with NBC. The interviewer asked him, “What is your opinion on the comparisons between you and the Shah?”

Sadat responded: “Honestly, I am puzzled. Such a comparison is completely baseless. Those who make it are people whose hearts are filled with hatred. You have seen the referendum results and how 100% of my people support my policies. So, how can such a comparison be made between me and the Shah? And what, other than hatred, can justify making it? Unfortunately, these people confuse opposition with hatred. They seek to tarnish my image and the image of Egypt. As for my image, it does not concern me, but I will not allow anyone to tarnish the image of Egypt.”

Ironically, Khaled El-Islambouli’s interrogation began in the same Maadi Military Hospital where Sadat’s body was lying. Heikal recounts, “One of the investigators tried to break his resistance by telling him that the president was not killed, but only wounded and was recovering.”

Although Khaled El-Islambouli was in a state of severe suffering, he was not deceived. He looked at the investigator with his sunken eyes, swollen from the beatings he had endured, and said, “You cannot deceive me. I fired thirty-four bullets into his body. Find something else to try to trick me with.”

Heikal adds that during the military trial of the accused, when Khaled El-Islambouli was asked if he was guilty or not guilty, his response was: “Yes, I killed him, but I am not guilty. I did what I did for the sake of religion and the nation.” The answers of the other defendants were identical. When asked who they had chosen to defend them as lawyers, they also answered: “Indeed, Allah defends those who believe.”

The military court sentenced five of the accused to death, with additional life imprisonment sentences for others, which were carried out. Only one person was acquitted.

Military Justice in Egypt

Several amendments have been made to Law No. 25 of 1966, which issued the Military Code of Justice, but military justice in Egypt remains specialized in specific cases. It applies, for example, to military personnel, students of military academies, those who attack military facilities, those who conspire with hostile entities, and those who fall into enemy captivity due to negligence or deliberate disobedience of orders. One of the most essential articles, for instance, is Article (106), which states in its first paragraph that “the death penalty for military personnel is carried out by firing squad, while for civilians, it is executed according to civil law.”

Regarding the selection of military judges, Article (54) states that “the appointment of military judges is made by a decision from the Minister of War, based on the recommendation of the Director of Military Justice.”

The Military Code of Justice takes a strict stance on theft involving military personnel. Article (136) states, “Anyone who steals from a dead, wounded, or ill soldier in a military zone, even if they are enemies, shall be punished by death or a lesser penalty specified in this law.”

As for reconsideration of validated sentences, Article (112) stipulates that “after validation, military court rulings can only be reconsidered by the highest authority above the validating officer, which is the President of the Republic.”

Regarding appeals against military rulings, Article (117) states, “No military court rulings may be appealed before any judicial or administrative authority in any manner that contradicts the provisions of this law.”

Constitutionality of Egyptian Military Justice

As for the constitutional stance on military justice in Egypt, Article (204) of the Egyptian Constitution, which was adopted following the 2019 constitutional referendum, states that “Military justice is an independent judicial authority, exclusively responsible for adjudicating all crimes related to the armed forces, its officers, personnel, and those in their equivalent ranks, as well as crimes committed by General Intelligence personnel during and because of service.”

Article (204) also clarifies that “A civilian cannot be tried before a military court except for crimes that constitute an assault on military facilities, military camps, or their equivalents, facilities under their protection, military or designated border areas, or military equipment, vehicles, weapons, ammunition, documents, military secrets, public military funds, or war factories. This also includes crimes related to conscription or direct assaults on its officers or personnel during the performance of their duties.”

The law specifies these crimes and further defines the other competencies of military justice. Members of the military judiciary are independent and irremovable, enjoying all the guarantees, rights, and duties granted to members of the civilian judiciary.

Legal scholars worldwide debate military justice. For example, Colombian legal scholar Federico Andreu-Guzmán expresses reservations about some countries adopting military justice, which he views as parallel to civilian justice.

In the first volume of his book Military Jurisdiction and International Law (2004), published in Switzerland by the International Commission of Jurists, Guzmán argues that “the issue of military justice goes beyond the judicial sphere to reach the core of the rule of law. In many countries, military justice and the team spirit that characterizes military courts have been transformed into a real tool in the hands of the military authority, used against civilian authority. Moreover, military courts often distance the armed forces and institutions from the rule of law and societal oversight.”

Ironies of Fate

Precisely forty years separated the death of Jehan Sadat in 2021 from that of her husband following her battle with cancer. She was buried next to him in the same place where he had laid a wreath of flowers on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier just hours before his assassination. In doing so, she became a witness to a site of immense tragedy, and undoubtedly, at that time, she had no idea that she was looking at the future resting place of both herself and her husband.