I had intended to perform Hajj in the year 1425 AH, corresponding to 2005 AD, with my sister accompanying me, as I would be her mahram. We applied through one of the Egyptian associations that organize Hajj and paid the required fees, which, as I recall, were around 15,000 Egyptian pounds each—approximately $2,600 per person at the time. However, after we received approval, I was offered a job opportunity in Saudi Arabia as a trainer for a video editing program. The offer came from Sony’s agent in Egypt during a visit to a broadcasting technology exhibition held in Cairo.

I felt torn—should I accept the job offer and miss the chance to perform Hajj that had already been approved for both me and my sister?

Even more concerning: would I be sinful if I missed this year’s Hajj, despite the means being available? Allah Almighty says in Surah Aal Imran: “…And [due] to Allah from the people is a pilgrimage to the House – for whoever is able to find thereto a way. But whoever disbelieves – then indeed, Allah is free from need of the worlds.” Would I also be guilty of severing family ties by depriving my sister of a rare opportunity to perform Hajj, since I was the only available mahram for her? Her husband had already performed Hajj before and could not afford the cost for them both this time.

A few weeks later, it became clear that my sister was expecting a child after a long wait, and therefore would not be able to travel for Hajj that year.

So we contacted the association, canceled our Hajj plans, and got our money back. I then obtained a visitor visa to Saudi Arabia through the employer in Riyadh, but it was stamped “Not permitted to perform Hajj this year,” since I was traveling to Riyadh less than a month before the Hajj rituals began. This is a common regulatory procedure meant to close any backdoor that some might use to perform Hajj without an official permit, to prevent overcrowding beyond the state’s organizational capacity.

I accepted the reality—until, two weeks before Hajj, three Egyptian colleagues at work informed me that they were going to perform the pilgrimage. Would I like to join as the fourth? I replied that I was officially prohibited from performing Hajj this year. They said it was merely a routine formality and need not apply strictly to someone already present in Saudi Arabia. I asked, “But how?” They said, “We’ll join a local Hajj group.”

I paid the required amount—4,000 riyals, which was around 6,000 Egyptian pounds at the time. This included transportation, lodging, and food—roughly a third of the lowest Hajj cost from Egypt. We received the required vaccinations, and a bus took us from Riyadh, driven for over 10 hours by a cheerful elderly Syrian man with a Bedouin accent I wasn’t used to. Years later, I realized he was probably from Deir ez-Zor. We covered around 800 kilometers until we reached the as-Sayl al-Kabeer area, the designated miqat for people from Riyadh.

I stepped off the bus at the first rest stop with swollen feet from sitting too long, but the joy I felt as I made the intention for Ihram and recited the Talbiyah—beginning the rites of Hajj and ‘Umrah together (qiran)—was indescribable.

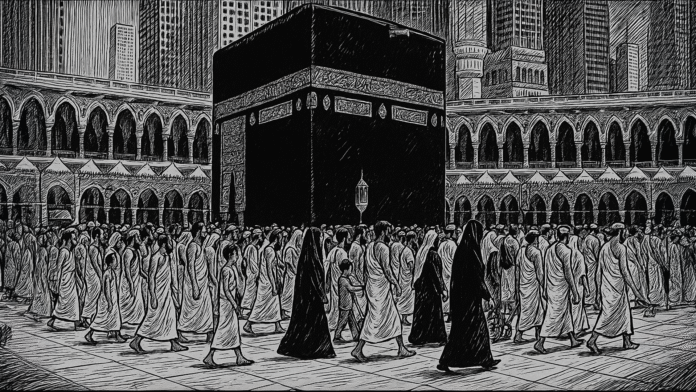

During the tawaf al-qudum (arrival circumambulation) around the Kaaba, and upon seeing the sacred House of God for the first time, I was surprised at how emotionally numb I felt. I had expected to shed tears of awe or joy, but none came. I was preoccupied with performing the rituals properly as described in the Hajj guidebook—as though I were in an athletic marathon, trying not to break any rules.

I saw dozens of people clinging to the Kaaba’s walls and its cloth, weeping and praying with intensity, but none of it moved me. I grew increasingly concerned about the state of my heart. Even when I had the chance to reach the Black Stone, I merely touched it with my hand and did not kiss it—avoiding the remnants of millions of lips that had kissed it before. I recalled the words of Umar ibn al-Khattab—after whom I would name my first son less than two years later—who said: “By Allah, I know that you are just a stone that can neither harm nor benefit. Had I not seen the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) kiss you, I would not have kissed you.”

I completed the first one or two circuits on the ground floor, then, to avoid the intense crowds, went up to the top floor. The crowds were thinner there, but the circuit was much wider and thus longer. There, I entered into a state of complete isolation from the surrounding waves of people, achieving a level of mental clarity I had never known before, and a spiritual contemplation carried by my exhausted feet, lightly brushed by the cold marble floor of January.

Then came the sa’i—walking and jogging seven times between the hills of Safa and Marwa. Most of the pathway was now covered in luxurious tiling, leaving only a small part of the original hilltops visible. I tried to seize moments to glimpse the Kaaba from afar. My reflections were only interrupted by an Asian janitor shouting in broken Arabic, “Move, pilgrim!” as he mopped the floor. I wondered: What must his relationship with God be for him to be chosen—among 2 billion Muslims—to serve in His House? And is the title “Hajj” he called me truly deserved in God’s eyes? I quenched the thirst of my questions with a cup of Zamzam water, whose containers were placed in every corner.

When the Day of Tarwiyah arrived—the 8th of Dhul Hijjah—I set off with my group by bus from Mecca to Mina. We prayed Dhuhr, Asr, Maghrib, ‘Isha, and Fajr there and spent the night. Then the bus transported us from Mina to Arafat after sunrise on the 9th of Dhul Hijjah, and we remained on the plain of Mount Arafat until the call to Maghrib prayer.

Then the bus took us from Arafat to the sacred site of Muzdalifah, moving at a painfully slow pace—like honey dripping—due to the congestion of tightly packed buses and swarms of pilgrims on foot. I spent the night there lying on a medium-sized mat that some Saudi brothers had spread beside the bus. We were all wrapped in the sky above us. Before resting, I had collected 49 pebbles from the grounds of Muzdalifah: 7 for throwing at Jamrat al-Aqabah on the Day of Sacrifice, and 21 for the three Jamarat on the second day of Eid, and another 21 for the third day.

While we were chatting, a young Saudi man suddenly called out: “Who named their phone’s Bluetooth ‘Ok bel bab’?” I didn’t understand what he meant at first. Then it dawned on me—“Maybe you mean Okbelbab?” He said, “Yes!” I replied, “That’s me! That’s my family name—‘Uqbelbab’—not ‘Okay at the door.’” We both burst into laughter.

On the Day of Sacrifice, throwing the Jamrat al-Aqabah was easy and smooth. Then we went to the Sacred Mosque to perform the Tawaf al-Ifadah and Sa’i between Safa and Marwah—rituals I had already practiced earlier during the arrival Tawaf.

But the next day—on the first day of Tashreeq, the 11th of Dhul Hijjah—I went with my three Egyptian coworkers to throw the three Jamarat (major, middle, and minor), and we were shocked by the massive crowds in Mina. We lost grip of each other’s hands and were swept away by the overwhelming current of people. I couldn’t see any of them again. I was crushed in the crowd, packed so tightly that there was no space between me and those in front or behind me. Panic started to set in. I couldn’t move forward, backward, or escape. I couldn’t even see my own feet—only feel them touch the ground now and then, sometimes stepping on unknown objects—perhaps a backpack or a rolled-up mat, left behind by poor pilgrims unable to afford shelter.

Suddenly, no fewer than ten elderly Indian pilgrims collapsed in front of me. I struggled not to fall on top of them or trample them. Others, however, began jumping over them like panicked monkeys fleeing a lion. I was filled with sheer terror—I genuinely believed my final hour had come.

Amid this sea of non-Arab Muslims, it struck me that we, as Arabs—even with our 400 million, Muslims and non-Muslims alike—are in fact a small minority within the global Muslim ummah of 2 billion. I searched desperately for a universal language that might bring calm to the chaos, but all I could think to do was cry out at the top of my lungs the Qur’anic word “Sakeenah!” (tranquility)—but sadly, no one in the frenzied crowd understood me.

I decided then and there to leave the area without completing this rite. But how could I escape this human flood? Eventually, I found myself near the back of a Saudi soldier, part of a long line of troops blocking further entry to the site. I tapped him on the shoulder and gestured that I wanted to exit. He allowed me through. I returned to my tent in Mina, wearing only one sandal—my other one had slipped off during the chaos, and I hadn’t dared to bend down to retrieve it.

Back at the tent, someone asked me, “Did you throw the Jamarat?” I replied, “Do I look like someone who did?” Everyone laughed, and I told them I wouldn’t perform this ritual—I’d appoint someone to do it on my behalf or offer a sacrificial animal instead. One man scoffed, “Appoint someone or offer a sacrifice? Are you a woman or an old man? How old are you?” I said, “35.” He laughed even harder and said, “Are you afraid of dying in a place like this? What a death that would be—any Muslim would long for it.”

His words stirred something in me. I gathered my courage and tried again, this time with a young Palestinian man. But as we neared the crowd, memories of the horror returned, and I turned back to the tent once more. The mock encouragement resumed.

On the third attempt, I went with three young Saudis and an elderly Egyptian man from Nubia. By then, the crowd had lessened. I threw the three Jamarat at lightning speed and returned quickly.

On the final day, I performed the farewell Tawaf (Tawaf al-Wada‘) and took the bus back to Riyadh. However, my joy was not complete because I missed the opportunity to visit the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina due to heavy rain. I made that visit years later, traveling from Doha during a training course I delivered at Riyadh Television in partnership with a British media organization. I took advantage of the weekend break to fly to the city of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ and stand at his grave to offer my greetings to him and his two companions.

In his article Are the Rites of Hajj Pagan? from his famous book A Dialogue with My Atheist Friend (1970), Dr. Mustafa Mahmoud delves into the depths of philosophical and religious inquiry. He presents—through his contemplative and luminous style—a question often echoed by skeptics: Aren’t the rituals of Hajj merely veiled forms of ancient pagan practices?

The dialogue begins theatrically, as Dr. Mahmoud describes his friend rubbing his hands with excitement and wearing a sly smile, as if preparing to land a knockout blow. Then he asks mockingly: “Isn’t circumambulating the Kaaba, kissing the Black Stone, throwing pebbles, running between Safa and Marwah, and the fixation on the number seven—just a continuation of old magical myths and superstitions?” He goes further, deriding the ihram garments, likening them to a “shroud on bare flesh.”

But Dr. Mahmoud, with the calm wisdom of a scholar, responds with the insight of the spiritually aware: “Don’t you also see that the laws of nature themselves revolve in eternal cycles? The electron orbits the nucleus, the moon circles the Earth, the Earth revolves around the sun, and the sun journeys through the galaxy—until the path ends at the Absolute Greatest… to God.”

So, if the lesser orbits the greater throughout the universe, why should man be an exception? We choose to circle the House of God—the first house ever established for mankind—while you revolve involuntarily within your solar system. Everything in this universe moves in circular motion, except God. He alone is still, eternal, and unchanging.

Dr. Mahmoud then delivers a striking analogy: “Aren’t you the same people who circle around an embalmed tomb in the Kremlin? Don’t you have rituals where you lay wreaths on a stone called ‘The Unknown Soldier’? So why blame us for throwing stones at a symbol of evil? Isn’t your own life a frantic run from birth to death? That’s exactly what we reenact in our Sa’i between Safa and Marwah—from non-existence to existence, and back again. A pendulum journey that mirrors the very cycle of life.”

As for the number seven—mocked by his friend—it holds within it mysteries of creation that boggle the mind: seven musical notes, seven colors in the light spectrum, seven electron orbits in the atom, the human fetus fully forming in the seventh month, and seven days in a week—across all languages and cultures. Isn’t this indicative of a deeper cosmic symbol far beyond a mere number?

Dr. Mahmoud reflects with tenderness: “Don’t you ever receive a letter from a loved one and kiss the page they wrote on? Does that make you a pagan?” We do not worship the Black Stone; rather, we honor its meaning, preserve its memory, and follow in the footsteps of the Prophet ﷺ, who held it with his blessed hands.

The rites of Hajj are not rigid rituals, but deeply thoughtful practices—ones that stir the mind, awaken the heart, and revive the conscience. As for the white garments of ihram, they are not just simple clothing; they symbolize shedding adornment, status, and wealth—just as we come into this world naked and leave it wrapped in a shroud. It is a silent declaration that no one stands above another before God: rich and poor, king and commoner alike.

Hajj, then, is not merely a personal act of worship—it is a global annual gathering, where souls and faces meet, where differences dissolve, just as believers’ spirits unite every Friday in congregational prayer. Such transcendent spirituality is far removed from paganism.

In a final moment of grace, Dr. Mahmoud invites his friend—just once—to stand with him on Mount Arafat, in the presence of millions, chanting “Labbayk Allahumma Labbayk” in over twenty languages, with hearts melting in humility and eyes overflowing with tears. If he witnessed that scene, he too would weep unknowingly and dissolve into the crowd—overwhelmed by a divine presence beyond description, before the Sovereign of all creation, the One who holds the keys to everything.

Hajj in Islam is a profound spiritual journey, one that combines devotion with transcendence, embodying the unity and cohesion of the Muslim ummah. It is the fifth pillar of Islam, made obligatory by God in the ninth year of Hijrah, as stated in the Qur’an (Surah Aal Imran):

“And [due] to Allah from the people is a pilgrimage to the House—for whoever is able to find thereto a way.”

The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ performed Hajj only once in his lifetime—the Farewell Pilgrimage in the tenth year of Hijrah—during which he taught the rites and delivered his famous sermon, completing the foundation of the Islamic faith.

Hajj is not a mere set of rituals—it is a comprehensive school of discipline, where the Muslim learns patience, humility, and detachment from worldly distractions. It fosters the sense of global brotherhood as Muslims from all corners of the earth gather in one place, performing the same rites, reciting the same talbiyah.

Among its greatest blessings: Hajj purifies the soul, forgives sins, and renews the covenant with God. As narrated in Sahih al-Bukhari, the Prophet ﷺ said: “Whoever performs Hajj and refrains from sexual relations and sinful behavior, will return as pure as the day he was born.”

Thus, Hajj remains an exalted spiritual journey that elevates the soul, cleanses the heart, and powerfully manifests the oneness of God and the unity of Muslims.

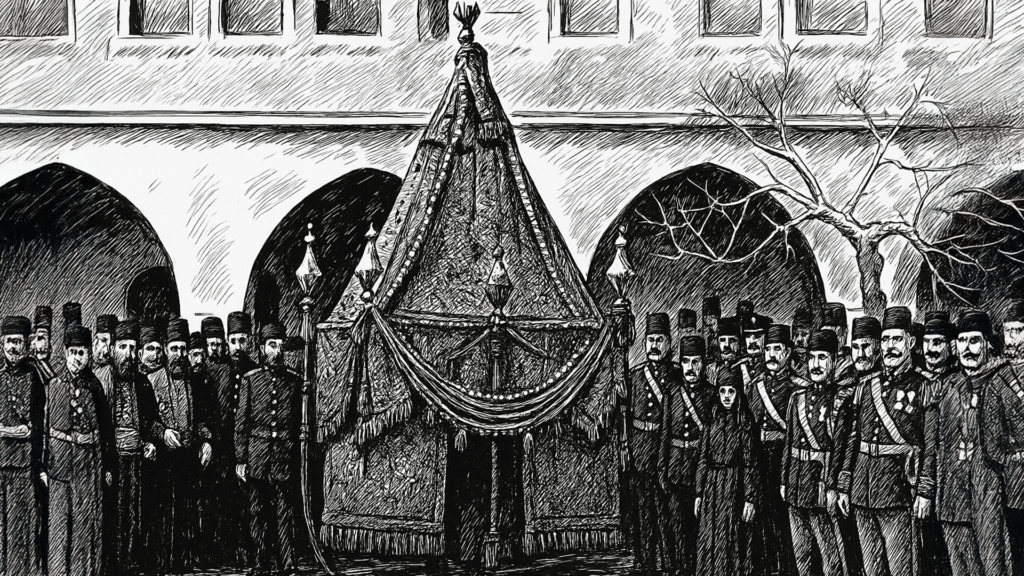

What caught my attention was an article on Al-Manar’s website about how Hajj used to be in the past—when the pilgrimage was an adventure fraught with danger. Caravans had to cross vast deserts, facing thirst and bandits along the way. The Ottoman Empire paid great attention to facilitating this spiritual journey, organizing Hajj caravans, building fortresses, digging wells, constructing inns along the routes, and appointing “Emirs of Hajj” to oversee the affairs of the caravans—some of whom even led accompanying military forces for protection.

These caravans included pilgrims from all social classes, from princes and the wealthy to the poor and destitute. The rich rode in palanquins on camels and horses, while the poor traveled on foot. The caravans were warmly received by locals and officials in the provinces they passed through, where the Emir of Hajj would receive endowments and gifts destined for the Two Holy Mosques.

The Ottoman state also sent with these caravans the Surra Humayun—imperial gifts distributed to the people and nobility of Medina. Leading the caravan was the Mahmal Sharif, a ceremonial replica of the Kaaba placed on the back of a camel, accompanied by the Sanjak—the banner of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

Caravans departed from various regions across the Ottoman Empire. The Shami caravan included pilgrims from the Levant, the Arabian Peninsula, Azerbaijan, the Caucasus, Anatolia, and the Balkans. The Egyptian caravan carried pilgrims from Egypt and North Africa, along with the Egyptian Mahmal and the new Kiswa (Kaaba covering). The Iraqi caravan included pilgrims from Iraq and Persia, and the Yemeni caravan comprised pilgrims from Yemen, India, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

Festivities would begin in a pilgrim’s household from the moment they were chosen in the Hajj lottery. Celebrations continued with singing, drums, and joyful ululations until the day of departure to the Hijaz. Preparations for the long journey involved packing clothes and dry food supplies such as duqqa (a sesame-based spice mix), dried molokhia leaves, sun-dried bread, and qarish cheese.

Egypt’s oral traditions were rich with songs and chants used to bid farewell to pilgrims and welcome them back. One popular folk line went:

“The pilgrim’s shawl edge is whiter than the sign / and whiter than milk, oh pilgrim, on your day of peace.”

The tradition of making the Kiswa (Kaaba cover) was among the most well-known annual customs, with Muslim rulers competing for the honor of providing it. The Mahmal caravan carrying the Kiswa and royal gifts would arrive overland from Egypt to Mecca amidst grand celebrations.

Thus, in earlier eras, the journey of Hajj was a unique spiritual, social, and cultural experience—reflecting the unity of Muslims and their mutual support, while also demonstrating the state’s dedication to enabling the performance of this great religious duty.

As part of Saudi Arabia’s modern preparations for the Hajj season, the Ministry of Hajj and Umrah outlined in its 2022 Guideline for Domestic Pilgrims the official conditions and procedures governing the performance of Hajj—aimed at ensuring the safety of pilgrims and facilitating the rites in an atmosphere of peace and tranquility.

The Ministry emphasized that applicants must be citizens or residents with legal status in the Kingdom, no older than 65 years, and priority is given to those who have never performed Hajj before. Applicants must also be fully vaccinated according to the Tawakkalna app and be in stable health to undertake the rites without hardship.

Registration is done through the online portal or the Eatmarna app, where applicants submit their personal information and choose suitable packages. They may also add companions to the same application. After registration ends, a random electronic lottery selects the approved pilgrims, who are notified via SMS and must pay the invoice within 48 hours of receiving it.

The Ministry strongly advises visiting a doctor before travel to ensure stable health and receiving all necessary vaccinations well in advance—especially for those with chronic illnesses. Physical fitness is encouraged, and pilgrims are advised to prepare a bag with essential medical supplies. Additionally, they must stay with their group throughout the journey and carry their smart Nusuk card and assigned accommodation address card at all times.

These measures reflect the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s commitment to providing a safe and well-organized environment for the Guests of the Most Merciful, ensuring that they can perform the Hajj rituals with ease and peace of mind.

According to Umm Al-Qura, the official gazette of Saudi Arabia, Prince Saud bin Mishaal bin Abdulaziz—Deputy Governor of the Makkah Region and Vice Chairman of the Central Hajj Committee—stated, during the launch of the 16th season of the campaign “Hajj is Worship and Civilized Behavior,” under the slogan “No Hajj Without a Permit,” that Hajj regulations will be strictly enforced on violators, and no one will be allowed to perform Hajj without an official permit.

He noted that in previous years, the campaign contributed to uncovering fraudulent Hajj operators and reducing the number of unauthorized pilgrims, which in turn improved the quality of services provided to the Guests of Allah and enabled them to perform the rites with comfort and tranquility. He also praised the Saudi leadership’s support and concern for the safety and security of pilgrims, commending the fatwa issued by the Council of Senior Scholars which prohibited performing Hajj without a permit, as it constitutes a violation of public order and harms legitimate pilgrims.

For his part, Director of Public Security, Lt. Gen. Mohammed Al-Bassami, announced that all security forces are fully prepared for the Hajj season. He indicated that officers had already begun monitoring the entrances to Makkah since the 15th of Shawwal, and no one will be allowed to pass the miqat without a valid Hajj permit. Field plans have also been developed to inspect accommodations in Makkah and identify violators, in coordination with the Ministry of Hajj and Umrah.

The Saudi Ministry of Interior has also announced the implementation of legal penalties against those who violate Hajj regulations. Anyone found within the boundaries of Makkah, the central area, the holy sites, the Haramain train station at Al-Rusaifa, or any of the security checkpoints or sorting centers—without a Hajj permit—will face penalties.

The ministry confirmed that a fine of 10,000 Saudi riyals will be imposed on any citizen, resident, or visitor caught in the designated geographic zone without a Hajj permit. If the violation is repeated, the fine will be doubled to 20,000 riyals. Furthermore, residents who are found violating the rules will be deported after serving the penalty, and banned from returning to the Kingdom for a period determined by the law.

Additionally, anyone caught transporting unauthorized pilgrims will face up to six months in prison, a fine of up to 50,000 riyals, and confiscation of the vehicle by court order. If the transporter is a foreign national, they will be deported and barred from re-entry for a period defined by law. The fine is calculated per violator transported, meaning penalties multiply according to the number of unauthorized pilgrims.

The timeless chant of Hajj—”Labbayk Allahumma Labbayk, Labbayk la sharika laka Labbayk”—will always remain a call open to every Muslim. However, necessity permits what is otherwise forbidden, and preventing harm takes precedence over securing benefit—as illustrated in the Qur’anic verse from Surah Al-Baqarah:

“They ask you about wine and gambling. Say, ‘In them is great sin and [some] benefit for people. But their sin is greater than their benefit.’”

Thus, Islamic law does not allow unrestricted access for all 2 billion Muslims to perform Hajj in a single year—such a scenario would result in chaos and endanger lives.