In this world where the streets buzz with classified ads and the screens shimmer with packaged dreams, it is no longer easy to distinguish between what we truly need and what we’ve been convinced we need.

We are the children of an era in which markets do not merely offer goods, but infiltrate our minds and tastes, stitching desires tailored to the designers’ visions, and shaping identities according to the sellers’ whims.

In this age, ownership is no longer an end, but a means of self-definition—one shaped by what we possess. It deceives us into feeling whole, only for us to wake and sleep wrapped in a masterful illusion that plants in us a constant sense of lack, measuring our worth by the number of items we own rather than the breadth of our hearts or the depth of our thoughts.

Paradoxically, this obsession spares no one. A child, before learning to read, knows how to ask; before writing their name, they can recite brand names. In their hands are screens that whisper: you exist only if you own what others do, you are loved only if you wear what they wear, and you are happy only if you have what they have.

Amid all this, parenting stands as an act of resistance in an age of commodification and branding—a rebellious value against a system that tries to convince us that the human being is merely a materialistic consumer, whose values are sold, not instilled.

Here begins the battle of awareness: a call to reclaim the compass shattered by the illusion of advertising, and the war of perception that demands we break free from the chains forged in the name of desire and possession. A moment to rebuild ourselves and our children, to draw a line between image and truth, between want and need.

For sufficiency is not weakness, and contentment is not surrender. They are the highest forms of freedom—not deprivation, but protection; not the enemy of ambition, but its moral anchor—so that a person does not become a slave to what they own, but confident in what they believe.

Reality

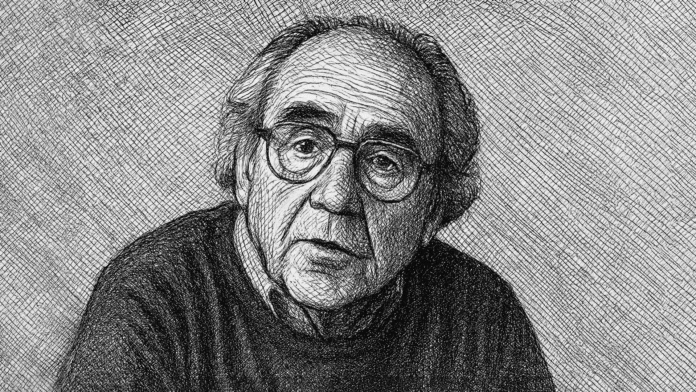

In the 1960s, Jean Baudrillard emerged as one of the leading thinkers of the new French intellectual generation. He was influenced by prominent figures like Roland Barthes—renowned for his studies on signs and symbols in culture and their role in generating meaning, and one of the foremost theorists of semiotics—and Henri Lefebvre, a key figure in urban theory with major contributions to understanding how cities evolve and impact social life.

Baudrillard served as a sociology professor at the University of Nanterre during the student unrest of 1968. He successfully combined philosophy and sociology, developing a critical lens on culture through unconventional approaches, which led to the formulation of new concepts on contemporary life. He was among the first to analyze how media and technology shape reality and identity.

One of his most influential works is Simulacra and Simulation (1981), in which he presented one of his most famous theories: the theory of simulation. This theory explores the relationship between reality and representation and argues that modern societies no longer experience true reality but are immersed in false representations that reproduce a virtual reality governed by images and signs.

At the heart of this theory is the idea that what we encounter in our daily lives—news, advertisements, concepts such as identity and power—no longer reflect an objective reality. Instead, they refer to a chain of copies and images that have lost their connection to any original, or perhaps never had one. This process unfolds in four stages: the representation of reality, the distortion of that reality, the concealment of the absence of reality, and finally, the creation of an image with no origin, known as a simulacrum.

Within this framework arises Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality—a deeply complex and disorienting condition in which modern humans unconsciously live. Hyperreality is a complete structure of representations that simulate reality to such an extent that they overshadow and eventually erase the original. The image becomes the sole reference, and reality is defined not by what is lived or experienced, but by what is produced and disseminated through media.

One of the most well-known metaphors for this is the map that precedes the territory—a symbolic story in which Baudrillard imagines a map created with such extreme precision that it eventually covers the entire land it was meant to represent. Over time, the territory erodes and disappears, leaving only the map behind. People cling to the map as their only reference, unaware that what they hold is merely a representation of something that no longer exists.

This simulation does not reveal reality; it hides it, offering a false copy that people mistakenly accept as truth.

Baudrillard also presents Disneyland as another model of hyperreality. While it appears on the surface to be a realm of fantasy and fun, it serves a deeper ideological function—it presents itself as a fantasy world to make the visitor believe that everything outside its gates is the real world. In truth, the outside world has also become a simulation.

Thus, Disneyland, the city of entertainment, becomes a system that reproduces illusion while hiding the fact that the world beyond its walls is no less artificial.

Baudrillard extends his analysis to even more sensitive domains, such as war. In his treatment of the Gulf War—later detailed in his provocative work The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (1991)—he argues that intensive media coverage, digital maps, and aerial footage transformed the war into a well-orchestrated television show that concealed blood, bodies, and the painful reality, replacing them with media content produced, broadcast, and consumed.

According to Baudrillard, the Gulf War became an unreal spectacle, transcending the actual event through screens that projected a new reality simulating what had supposedly taken place.

In everyday life, shopping malls offer yet another example. They are not merely places for purchasing goods; they are fully engineered spaces designed to simulate cities—but cities stripped of chaos, heat, nighttime, and poverty. These are controlled environments governed by desire and spending, convincing visitors they are in a natural world, while in fact they live inside a model detached from real social life.

All these examples point to one conclusion: we no longer live in a verifiable, authentic world. Instead, we inhabit a domain of simulations, symbols, and images—a hyperreal world that appears familiar and convincing, yet is, at its core, a copy without an origin.

Thus, simulation is not just a representation of reality—it becomes reality itself, swallowing truth and immersing humanity in a vortex of images that refer only to other images.

Consumption

Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality is deeply intertwined with consumer culture. He believed that consumption was no longer a simple act of exchanging goods or fulfilling material needs—it had become a core mechanism in generating a false world of meanings and symbols. In this world, images proliferate and truth is replaced by dazzling appearances that appeal to desire, not necessity.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy analyzes Baudrillard’s view of the consumer society, noting that in modern societies, goods are no longer consumed for their utility or economic value but for their symbolic value—for what they represent rather than what they do. Cars, phones, shoes, and even clothing styles have become signals that define the individual within a complex web of signifiers. This produces a false identity that can be bought and sold like any other commodity.

The encyclopedia further explains that this pattern of consumption generates a state of collective alienation, as individuals live in a world ruled by the value of signs rather than the value of things. It is a world shaped by identification with images, not genuine experience. Consumption becomes a form of symbolic enslavement—it offers the illusion of freedom while entrenching invisible shackles.

One striking example of this hyperreal consumer era is the toy Labubu, which serves as a remarkable case study of how a simple product can evolve into a cultural and economic phenomenon that transcends borders.

According to a report by Meltwater, Labubu began as an art design by Hong Kong-based artist Kasing Lung, part of a series of illustrations known as The Monsters. It quickly transformed into a mass-market hit when adopted by the Chinese company Pop Mart and incorporated into its blind box ecosystem, a model built on emotional addiction and the thrill of surprise.

The same report noted that between January and May 2025, the keyword “Labubu” appeared more than 876,000 times across media outlets and social media platforms—marking a 76% increase in visibility and a 137% spike in engagement compared to 2024.

According to The Business Times, the Labubu product line alone accounted for roughly a quarter of Pop Mart’s total revenue in 2024. That translates to hundreds of millions of dollars in profit from a single product. From 2023 to 2024, Pop Mart’s overall sales soared to around $1.8 billion, with Labubu at the heart of this meteoric rise.

And the success wasn’t confined to China—Labubu became a global craze. Collectors camped outside stores, paid inflated prices for limited editions online, and turned this toy into a collective obsession rather than a casual purchase.

This tiny toy, with its quirky features, generated annual revenues exceeding $400 million, positioning one company to challenge global giants—not because of the toy’s utility, but because of what it represented: identity, symbolism, and emotional connection. This underscores the paradox of modern consumption—we no longer buy things for their function but for their symbolism, their rarity, and the beautiful illusion they offer in a sealed box. We may not know what’s inside, but we know we want it.

People no longer buy the toy because it’s a doll, but because it’s a symbol of uniqueness, a token of belonging to a particular visual taste, and a form of unpredictable discovery.

As Professor Yu Yiqun from Fudan University explains, Labubu embodies what many call coded childlike rebellion. Collectors don’t just purchase a product—they express themselves through it. It’s a toy that offers identity as much as it offers entertainment.

Reports from AP News and the Wall Street Journal add further complexity: people sleep outside stores, hire others to wait in line for them, and spend outrageous amounts on rare editions of Labubu sold online. Some governments, like China’s, have raised alarms about the impact of this craze on social behavior and personal finances.

All of this points to the idea, as noted by Meltwater, that Labubu is not just a toy—it represents hyperreality in Baudrillard’s sense: a reality in which images are produced and consumed as truth, where symbols outweigh substance, and appearances precede essence.

Labubu thus reveals a deeply symbolic cultural moment—one that encapsulates the crisis of consumption in the age of the image, and illustrates how reality has shifted from lived experience to a stream of seductive signs we chase and collect, believing we possess ourselves, while in fact we merely grasp a shadow of what we once thought was real.

Dr. Abdelwahab Elmessiri, as cited in an article by Salman Bounaman published by the Nama Center for Research and Studies titled In Critique of the Contemporary Consumer Model, argues that modern consumption is no longer merely an economic activity to meet needs, but has become an ideological tool aimed at shaping human consciousness and dismantling spiritual and cultural structures.

According to Elmessiri, we now face a vast media and advertising apparatus that doesn’t just promote products—it promotes a specific worldview, one in which happiness is reduced to ownership, and success is measured by possessions, not meaning.

Through this lens, Elmessiri shows how advertising culture manufactures desire, generates emptiness, and feeds a perpetual illusion of inadequacy—turning humans into anxious, self-absorbed consumers detached from their communities and immersed in a false vision of life.

As Bounaman relates, Elmessiri sees this system as a modern form of imperialism—seeking to infiltrate and unravel societies from within by stripping them of their values and replacing them with a materialist, alienated culture.

Therefore, Elmessiri warns against importing this model without critical awareness, as it leads to societal fragmentation, loss of meaning, and a growing gap between the individual and their community—leaving behind a spiritual void that no commodity, however valuable, can ever fill.

Parenting

Children are among the most vulnerable groups when it comes to falling into the trap of consumerism. Due to their emotional and psychological nature, they have less ability to distinguish between need and desire, and are more easily influenced by the flashy images, advertisements, and appearances presented to them.

Therefore, parenting is not just casual guidance—it is a deep responsibility to correct this innate inclination toward possession and to shape the child’s awareness so that they understand their worth is not measured by what they own, but by what they know, feel, and believe. A conscious family forms the first line of defense against a ruthless consumerist world, instilling in children from an early age values like contentment, patience, and discernment between necessities and luxuries.

According to the article My child is materialistic and loves gifts and money… What should I do?! published on Al Jazeera’s website, children become materialistic easily due to a mix of psychological and social factors. Chief among them, as researcher Marsha Richins points out, is social anxiety during middle school, when the child feels an urgent need to assert their identity among peers.

In this context, objects become tools for proving status and belonging. The child starts to measure their self-worth by what they have rather than who they are. The situation becomes more complicated when children are rewarded with gifts or money for good behavior, reinforcing the idea that happiness can be bought and that satisfaction is only achievable through consumption. Over time, these psychological mechanisms become entrenched behavioral patterns that are hard to change in adulthood—unless conscious parenting intervenes early to link desire with awareness, and happiness with meaning, rather than childhood with possession.

In a time when advertisements race to shape human taste and needs, and childhood is fed on desire rather than necessity from the earliest moments, contentment seems like an impossible virtue, and raising children on simplicity and sufficiency becomes a form of cultural resistance.

In this light, Mona Khair offers a thoughtful perspective in her article How to Raise a Non-Materialistic Child?, restoring the importance of contentment in the age of consumption. She argues that contentment is no longer just a parenting choice—it has become a preventive necessity against the psychological pressures children face in the era of social media.

Contentment, Khair explains, is not the opposite of ambition but a form of education that teaches discernment between true needs and fleeting temptations, between calm desire and anxious impulse. Here, parents play a crucial role in modeling balanced behavior: not chasing every trend, not equating happiness with appearances.

Contentment begins at home—with the language parents use, their daily choices, and how they handle money, gifts, and purchases. Every consumer moment can become a lesson in balance: Are we buying because we need it or just because we want it? Do we reward good behavior with material goods, or with meaningful recognition and verbal appreciation? This is how consumption becomes a pedagogical act and controlling it becomes a way to instill deeper values of happiness and gratitude.

In prophetic parenting, contentment is tied to true richness. As the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ said, “Richness is not in having many possessions, but richness is being content with oneself.” This means a child won’t be content just by being denied purchases, but when they are truly convinced that what they already have is enough, and that what they lack is not essential.

There are many practical ways to cultivate satisfaction and detachment from materialism in children. One of the most effective is training them to practice daily gratitude—by thanking God for His blessings—so that they become thoughtful before asking, reflective before owning, and satisfied before desiring.

Contentment is not deprivation, nor is teaching it repression. It is a path to awareness and insight. When a child learns to distinguish between need and want, and to value meaning over appearances, they develop immunity against excessive material attachment.

This kind of upbringing sows balance in the soul and teaches that happiness is not bought, that true joy comes not from the outside, but from within—from the inner conviction that what one has is enough, and that worth is not measured by possessions but by pure intentions and broad horizons.

So when this child enters a world full of glowing storefronts and endless offers, they will not lose their way—because their inner compass will continue to point toward what is truer and more lasting.

They will know that their value does not lie in what they own, but in the knowledge they carry, the love they live, and the convictions they uphold. In that moment, contentment will not appear as renunciation or austerity, but as it truly is: a spiritual strength that liberates a person from the bondage of things, grants serenity that many wealthy people lack, and offers peace that precedes a full pocket—and remains when it is empty.