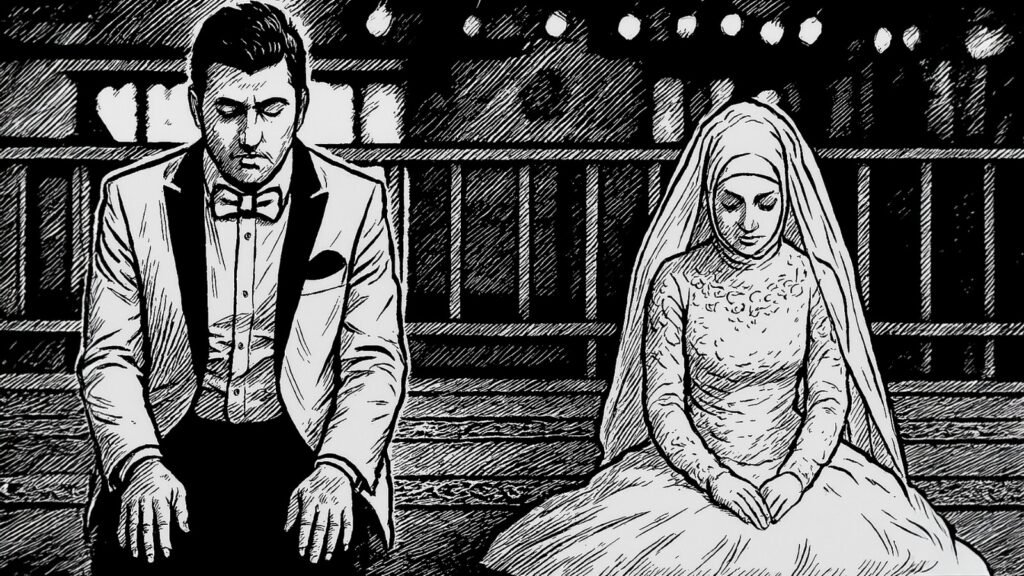

The term “civil marriage” sparks wide controversy in Arab societies, particularly when raised in a culturally and religiously conservative context, where the institution of marriage is viewed as a legitimate bond with religious, social, and legal dimensions.

In contrast, other countries adopt different models of marriage, based on a civil contract regulated by the state, without requiring any religious authority to validate the union.

In recent years, the concept of civil marriage has increasingly surfaced in public discourse, through media, TV series, and personal stories shared by celebrities. This has opened the door to numerous questions about its acceptance or rejection, and its impact on family structures and legal systems in the Arab world.

Between those who view it as a threat to identity and others who see it as a means to secure rights in pluralistic societies, the question remains whether civil marriage can find a place in the Arab legal and social framework, and how its nature might clash with the cultural and religious distinctiveness of these communities.

Dr. Salwa Al-Mulla, in her article published in Al-Sharq newspaper, stirred deep controversy around the issue of civil marriage—but it was not purely a legal or jurisprudential debate. Rather, it resembled a cultural and identity-driven outcry against changes she perceives as internal threats to our societies.

Al-Mulla did not view civil marriage as merely a legal contract between two parties, but as a gateway to dismantling an entire value system, one built on entrenched religious concepts and traditional understandings of family and lawful bonds between individuals.

In her article, the rejection of civil marriage appeared to go beyond jurisprudential texts to broader concerns: the fear of detachment from identity, the dissolution of boundaries between religions, and the importation of foreign models detached from the Arab-Islamic context. Al-Mulla expressed concern over the phenomenon of some Muslim women marrying non-Muslims under civil frameworks, outside the conditions of Islamic marriage contracts—often promoted by well-known and influential figures—without regard for the jurisprudential and legal complications such unions might entail, such as issues of inheritance, the woman’s waiting period (`iddah), and the religion of the children.

In this context, Dr. Al-Mulla viewed what is happening not merely as a shift in social relationship patterns, but as a subtle attack on human nature (fitrah), targeting identity by redefining concepts like family and lawful union, and replacing them with civil versions imported from the West.

She expressed regret that societies with rich histories, cultures, and civilizations are retreating from their principles under the pressure of modernity, secularism, and globalization—adopting hybrid models lacking clarity and stability. She argued that holding on to Islamic and Arab identity is not a regressive stance, but rather a legitimate cultural resistance against the dissolution of identity.

What the author presents is not simply a position on civil marriage, but a call to reclaim the question of identity in a time of value fluidity—and to rethink whether modern life models are being imposed upon us, or chosen with awareness and responsibility.

Civil marriage, in its legal definition, is a contract entered into between two parties before an official authority of the state, without the need for religious involvement or sectarian rituals. It is documented in the presence of two witnesses and based on official documents that verify the identity and social status of the parties. Civil marriage is recognized in most countries around the world as the primary legal means of registering a marital relationship.

The controversy, however, is not only about the religious validity of such marriages, but also about the precise distinction made by Qatari legislators between the legal effects of the contract and its religious effects. According to Law No. (21) of 1989 regulating the marriage of Qatari nationals to non-Qataris, any marriage contract concluded abroad that does not comply with the conditions and procedures outlined in the law is not legally recognized, cannot be documented within the country, and produces no legal effects that can be relied upon before official bodies.

In other words, under such a contract, the foreign spouse cannot obtain residency, and the Qatari spouse is not entitled to the social allowance or any of the privileges granted to citizens whose marriages are officially recognized by the state. The law even goes further by imposing administrative and disciplinary penalties on violators, including dismissal from public office, termination of scholarships, or denial of public housing—measures aimed at regulating behavior in alignment with public interest and the state’s public order.

However, these legal provisions do not negate the religious validity of the contract. A fatwa published on the Meezan website clarified that, under Qatar’s constitution—which recognizes Islamic Sharia as a principal source of legislation—a marriage contract that meets its Islamic pillars is religiously binding, even if concluded outside the state’s legal framework.

In Islamic law, marriage is not merely an administrative procedure; it is a solemn covenant that forms the foundation of the family, preserves lineage, and entails rights and responsibilities that are not nullified by the absence of legal documentation.

Therefore, obligations such as maintenance (nafaqa), dowry (sadaq), and custody (hadanah) remain valid from a Sharia perspective. These rights cannot be dismissed simply because the contract contradicts the procedures of civil law. A contract that satisfies the basic religious pillars—mutual consent, guardian (wali), witnesses, and dowry—remains valid despite procedural shortcomings.

Nonetheless, strict requirements exist for the religious validity of a marriage conducted abroad: it must be officially registered in the country where it was concluded and follow that country’s legal procedures. Unregistered marriages—those not formally documented—are recognized neither religiously nor legally, in order to prevent fraud and safeguard family stability and legal rights.

It is noteworthy that the Qatari legislator used the phrase “not recognized”, while other Arab laws, such as Egyptian law, use the term “claim not heard” when a marriage is informal and undocumented. This is a procedural expression meaning the court will formally reject the claim, not that the relationship itself is denied. It reflects a social policy intended to encourage documentation, not deny marital bonds when their pillars are established.

In conclusion, this distinction between the legal and religious effects of foreign marriage contracts highlights one of the most significant tensions between the modern state, which seeks to regulate human relationships within clear legal frameworks, and Sharia, which emphasizes the sanctity of the marriage contract when its essential conditions are met—even if some procedural elements are lacking.

The central challenge remains: how to reconcile respect for religious rulings with the demands of public interest, as managed by the state amid ongoing social change.

The Family Documentation Department in Qatar has organized the handling of personal status matters for residents, who make up a significant portion of the population. In principle, Qatari law does not prohibit non-citizens from marrying on its soil—whether between individuals of the same nationality or different ones—but completing the marriage requires adherence to specific procedures designed to ensure both parties are legally and religiously eligible to marry.

If one or both of the spouses reside in Qatar, the first step is to submit a marriage application to the competent Family Court—whether the Sharia court for Muslims or the appropriate court for non-Muslim communities. However, the application will not be processed without a set of essential documents, including: a copy of the passport, valid residency permit, a no-objection letter from the embassy of the foreign spouse (if one party is non-Qatari), a medical certificate confirming that both parties are free of infectious diseases, and certificates attesting to marital status (single, divorced, widowed), depending on the case.

This documentation process is more than a mere administrative step—it is the primary guarantee of both parties’ rights, especially in the event of disputes, divorce, or relocation of one spouse to another country. Only the officially documented contract is valid for issuing birth certificates, opening hospital files, and processing residency, education, and employment formalities.

Since Qatar adopts Islamic Sharia as a primary source of legislation, courts ensure that any marriage contract fulfills the essential conditions of an Islamic marriage: offer and acceptance (ijab and qabul), presence of a guardian (wali) for the woman, two just witnesses, and a dowry (mahr). If the marriage was civil or conducted abroad, it must be certified by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and translated into Arabic before the Qatari court will consider validating it.

While civil marriage remains controversial in many Arab societies—especially where family law is rooted in religious authority—it is the official legal framework for marriage in many countries, and in some cases, a civil contract is mandatory before any religious or social ceremony can be recognized.

In France, for example, civil marriage is the only legally recognized form. A religious marriage has no legal standing unless the couple is first married civilly at the municipality, reflecting the country’s strict secular model and full separation of religion and state.

In Germany, the law requires the civil marriage to be completed at the Civil Registry Office. Any religious ceremony is purely symbolic and carries no legal effect until the civil procedure is completed.

In Italy, civil marriage is also mandatory unless a religious (usually Catholic) ceremony is conducted and later recognized by the civil authorities—an arrangement known as a concordat marriage, based on the Lateran Treaty between the state and the Catholic Church.

In Canada, there is greater flexibility. Civil marriage is officially recognized regardless of religious or sectarian background. Canadian law allows couples to choose the type of ceremony—religious or civil—so long as it is registered with the proper authorities.

In the United States, where the legal system is decentralized, marriage laws vary by state. However, civil marriage is the prevailing model, whether performed in court or by a licensed officiant, and is crucial for legal recognition of the union.

In the Arab world, Lebanon presents a unique case. Although there is no legal framework for civil marriage within the country, many Lebanese travel to countries like Cyprus to marry civilly, then register the marriage with Lebanese authorities, which recognize it as a valid legal contract conducted abroad.

In Tunisia, the state has officially recognized civil marriage as the standard form of marital contract. Marriages are documented at municipalities, with the option of holding religious ceremonies afterward for those who wish—but without any legal obligation or recognition attached to them.

In this context, Cyprus has emerged as a preferred destination for many Arabs—especially from Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, and Egypt—who cannot legally contract a civil marriage in their home countries due to the absence of legal provisions or family opposition. Thanks to its simple procedures and fast processing, Cyprus has become a legal haven for this type of marriage.

We may encounter works that seek to carve out a space for civil marriage within Arab societies, such as Talal Al-Husseini’s book Civil Marriage: Right and Contract on Lebanese Soil (2013). In it, the author raises a profound issue that goes beyond legal jurisprudence to explore broader questions about the relationship between the individual and the state, sectarian identity and citizenship, and the legal text and its historical and social contexts.

While the book is grounded in a detailed analysis of Decision 60 L.R., issued by the French High Commissioner in 1936, and deconstructs its language and implications, it also touches on a more complex issue: Can a person exercise the right to marry outside of traditional sectarian frameworks without being accused of abandoning religion or defying social norms?

In his structured argument, Al-Husseini attempts to demonstrate that a legal foundation—though often overlooked—does exist that allows for civil marriage to be conducted on Lebanese soil without the need to travel abroad or belong forcibly to a recognized sect. He draws on logical, historical, linguistic, and philosophical tools to expose contradictions within the prevailing legal discourse and to affirm the rights of a segment of citizens who have no sectarian affiliation, even though they are recorded in official state registries.

However, despite the legal coherence and rights-based logic of this argument, it faces serious objections that cannot be ignored. Some argue that civil marriage, as proposed in this context, is not merely a procedural alternative but rather a challenge to the very identity of Lebanese society, which is based on a delicate balance of religious and sectarian pluralism.

From this perspective, the idea of separating personal status laws from religious authority is seen as a direct threat to historic religious institutions and to the value system that has governed family relations for centuries. This concern is not without merit in an environment where religious identity is deeply interwoven with the legal, political, and social structures.

Moreover, for some, the promotion of civil marriage is not viewed in isolation but rather as part of broader transformations across the Arab world. It is perceived as a form of cultural alienation or emulation of secular Western models that do not necessarily align with the makeup of conservative or Islamic societies. Therefore, the call to legalize civil marriage may be interpreted as part of a wider project to reshape values and norms, not merely a demand to expand legal options.

On the other hand, it is undeniable that freedom of belief and affiliation is a core principle of modern constitutions and international human rights declarations. From this standpoint, granting legal recognition to the right of those without a sectarian affiliation to marry under a civil framework does not abolish the rights of religious communities or impose a single model on all. Rather, it offers a necessary balance between public interest and respect for diversity within a pluralistic society.