In light of the accelerating geopolitical shifts around the world, the need has become increasingly urgent—especially for Muslims, including refugees and the oppressed—to seek alternative homelands that not only offer the essentials of a dignified life, but also respect their values and principles, and support their just causes, foremost among them, in the eyes of most Muslims, the Palestinian cause.

Migration today is no longer merely a physical relocation from one place to another; it has become an existential decision that touches the very core of identity, belonging, and dignity. Thus, evaluating potential destinations can no longer rely solely on factors like income or stability. A country’s stance on Palestine has emerged as a deeply significant moral criterion, especially amid the growing waves of normalization and the rise of narratives that criminalize resistance and equate it with terrorism.

Choosing among countries has proven to be a highly complex task, with positives here often accompanied by negatives there. However, our selection of the most suitable nations was based on a set of comprehensive criteria—those that combine advanced economic and social systems with official and popular positions supportive of Palestinian rights and opposed to Israeli domination.

To ensure objectivity, we delved—within the scope allowed—into the migration and naturalization laws of several countries, without claiming to be exhaustive. Our evaluation also drew upon the Human Development Index (HDI) issued by the United Nations Development Programme, which measures a country’s development level across three main dimensions: health, measured by life expectancy at birth; education, assessed through average and expected years of schooling; and standard of living, calculated using gross national income per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity.

This index classifies countries into four categories: low, medium, high, and very high human development.

Our top five selections—Malaysia, Turkey, Ireland, Spain, and Sweden—stood out for meeting both advanced development standards and maintaining politically and ethically positive stances on Muslim issues, particularly the Palestinian cause, while acknowledging that every country has its mix of strengths and drawbacks.

In this context, we explore the experiences of these countries from a Palestinian perspective, aiming to understand how their migration and naturalization policies intersect with their support—or neutrality—regarding the struggles of peoples seeking dignity and freedom. After all, the two-state solution promoted by some pro-Palestinian states is viewed by many Palestinians as more of a nightmare than a dream. The geographic space promised to them from historic Palestine after the 1948 Nakba appears as scattered fragments of land surrounded on all sides by Israel.

Malaysia

In a world where many Muslims seek a safe haven that balances quality of life with principles, Malaysia stands out as a unique destination that offers both a decent standard of living and a firm political stance on Islamic causes—foremost among them, the Palestinian issue.

Despite its relatively small population of 35 million—65% of whom are Muslims, approximately 22 million—Malaysia ranked 67th globally in the 2023 Human Development Index, with a score of 0.819, placing it in the category of countries with very high human development.

This progress is evident in daily life: the average annual income per capita is around $14,000, with a notably low unemployment rate of 2.9%, effective healthcare services, and a life expectancy of 75 years—all indicators of social and economic stability.

What most distinguishes Malaysia in the eyes of many Muslims is its legal system, which draws heavily from Islamic law in many aspects, in addition to its unwavering stance on the Palestinian cause. Dr. Mohsen Mohammad Saleh stated in the 2020–2021 Palestinian Strategic Report published by the Al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consultations in Beirut that Malaysia is one of the few Asian countries that has consistently supported Palestine both officially and popularly.

This support is not recent—it stems from deeply rooted Islamic values within Malaysian society, clearly expressed by former Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad (known as “Mohader bin Mohamad” in Jawi), who described Israel as an illegitimate occupying entity during his speech at the United Nations in 2018—a position that has remained firm under subsequent governments despite international pressure.

Popular support for the Palestinian cause in Malaysia is no less significant than the official stance. Organizations such as the Malaysian Consultative Council for Islamic Organizations (MAPIM) are actively involved in coordinating the efforts of dozens of Islamic NGOs in aid campaigns, advocacy, and awareness conferences regarding Palestine, playing an effective role in supporting the Palestinian people.

According to the Qatar News Agency (QNA), Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim condemned in 2025—during his meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron at the Élysée Palace in Paris—“the ongoing bombardment and atrocities committed by the Israeli occupation against civilians, women, and children in Gaza,” describing it as a shame on the international community to be unable to put an end to it.

He also expressed his support for the French initiative for a two-state solution, as well as efforts to seek peace in the Middle East, and called for the urgent delivery of humanitarian aid to the residents of Gaza.

On the level of immigration and residency laws, Malaysia has developed its digital infrastructure. According to the official website of the Malaysian Immigration Department, under the Ministry of Home Affairs and based on the Immigration Act 63 of 1959, foreigners can apply for visit, work, and long-term stay visas—facilitating the integration of students, professionals, and investors.

Although Malaysia is not a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention on Refugees, in practice it demonstrates a degree of leniency toward refugees from Syria, Palestine, and Burma. Its regulatory policies are strict but transparent, offering a legal environment that is manageable for those who comply with the law.

While acquiring Malaysian citizenship is not an easy process—as stipulated in the Federal Constitution—recent constitutional amendments passed in March 2024, particularly those allowing mothers to pass on citizenship to their children, reflect a move toward greater fairness and modernization in some areas.

In sum, Malaysia represents a balanced model for Muslims seeking a stable life that combines decent living standards with political dignity. It is a country that does not compromise on values and offers residents the opportunity to live in an open and safe environment—without having to sacrifice their identity or their voice in the face of injustice.

Turkey

Despite the ongoing economic and social challenges Turkey faces, it remains an attractive destination for migration—especially for Arabs and Muslims seeking a life that combines cultural affinity with opportunities for employment and stability.

Strategically located between East and West, Turkey is home to approximately 86 million people and is classified among the countries with high human development. According to the United Nations Development Programme’s 2023 report, Turkey scored 0.853 on the Human Development Index, ranking 51st globally.

The same report shows that Turkey performs well in indicators such as education, health, and income, although still below the standards of Western European countries.

The average annual income per capita is about $16,700, with a monthly salary ranging from $1,000 to $1,100, and a minimum wage of around $630.

However, high inflation—ranging from 40% to 50% in 2025—has weakened purchasing power and made the cost of living increasingly burdensome, especially for the middle and lower classes in major cities.

In terms of employment, foreigners in Turkey are subject to a regulated legal framework. One cannot work without an official permit issued by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, as outlined in International Labor Law No. 6735 of 2016.

Turkey offers various types of work permits, including temporary, permanent, and self-employment permits. Those wishing to work independently must demonstrate the feasibility and economic impact of their business, according to official regulations published on the Invest in Turkey website.

Additionally, individuals under temporary protection—such as Syrians and Palestinians—are eligible for a work permit six months after receiving a protection card, though they do not enjoy the full rights granted to permanent residents.

Regarding citizenship, Turkish Nationality Law No. 5901 (2009) outlines several paths to naturalization, including residency for five years, marriage to a Turkish citizen, or investment. Foreigners can apply for citizenship by purchasing property worth at least $400,000, provided the funds are transferred via a Turkish bank and the property is registered in their name through the General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre. However, under the amended Article 35 of Turkish Property Ownership Law No. 2644, citizens of certain countries—including Syria, Cuba, Armenia, and North Korea—are prohibited from owning property in Turkey.

Other citizenship pathways include depositing at least $500,000 in a Turkish bank for a minimum of three years or investing the same amount in government bonds or investment funds.

Citizenship can also be granted to those who create jobs for 50 Turkish citizens. These routes do not require prior residency in Turkey; citizenship is granted directly by presidential decree without going through the usual stages of naturalization.

Due to the complexity and variety of Turkish legal procedures, it is not possible to cover all details here. However, two of the most essential official websites are the Presidency of the Republic of Turkey Investment Office and the official e-Government portal (e‑Devlet).

For complaints or suggestions regarding public services, individuals can contact the Turkish Presidential Communication Centre (CİMER), which is a key communication channel between the public and the state.

Notably, Turkey allows dual citizenship and does not require Turkish language proficiency for naturalization via investment, making it a relatively flexible option for those seeking a second nationality.

As for Turkey’s stance on the Palestinian cause, it has undergone historical shifts. Initially, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk—the founder and first president of the modern Republic of Turkey—relations were cold, and Turkey became the first Muslim-majority country to officially recognize Israel in 1949 following the 1948 Nakba.

However, this trajectory changed dramatically with the rise of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2002, when President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan adopted a strongly pro-Palestinian rhetoric and vocally condemned Israeli occupation policies.

At the 2009 Davos Forum, Erdoğan declared that Turkey could not remain silent about the killing of children on the beaches of Gaza—referring to the tragic case of Palestinian child Huda Ghalia, who witnessed the death of her father, siblings, and aunt in an Israeli naval strike in 2006.

Tensions between Turkey and Israel escalated after the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident, in which Israeli forces killed 10 Turkish activists en route to break the siege on Gaza. This led Turkey to expel the Israeli ambassador and freeze military cooperation.

Although diplomatic relations resumed in 2016, Turkey’s political rhetoric in international forums remained clearly supportive of Palestinian rights. Ankara backed UN resolutions opposing settlements and rejected the recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

Nevertheless, some Palestinians view Turkey’s position as contradictory, citing continued growth in trade between Ankara and Tel Aviv. This raises questions about the consistency between Turkey’s political discourse and its economic policies.

That said, Turkey has undeniably provided tangible humanitarian aid to Gaza through organizations such as the Turkish Red Crescent and the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (IHH), and has funded projects in the West Bank—making it, in the eyes of many, a country that still stands—at least partially—with Palestine at a time when many others have withdrawn.

Ireland

Ireland is considered one of the leading European countries that combine a high quality of life with clear ethical stances in foreign policy—particularly in its steadfast support for the Palestinian cause.

According to the United Nations Development Programme’s 2023 report, Ireland ranks 11th globally on the Human Development Index, with a score of 0.949, placing it among the countries with very high human development.

The country’s GDP is estimated at around $594 billion, and the average annual income per capita exceeds $100,000 (based on purchasing power parity), making it one of the highest-income countries in the European Union.

Despite the high cost of living—especially in the capital, Dublin—Ireland offers a high-quality healthcare system, advanced education, and a level of social security considered among the best in Europe.

What sets Ireland apart in the eyes of many migrants—especially Muslims and Arabs—is not limited to these economic and social indicators but extends to what Brendan Ciarán Browne described in his study Reading Irish Solidarity with Palestine Through the ‘Unfinished’ Irish Revolution as “a struggle-consciousness rooted in the Irish colonial experience.” Ireland is one of the few countries that view the Palestinian cause through a historical and moral lens, shaped by its own experience of resisting British occupation.

As Browne noted, the symbolism of hunger strikes that united Irish figure Bobby Sands with Palestinian Khader Adnan is just one reflection of the deep intersection between the two causes.

He adds that this solidarity is not just a slogan but has translated into real initiatives—from flotillas breaking the Gaza blockade to Irish doctors and academics working in the occupied Palestinian territories.

While the author cautions against excessive idealization of the Irish model—pointing to the incomplete nature of Irish independence due to continued British control over the North—he notes that the Irish people and civil society have remained ahead of the government, which he describes as more performative than substantively committed, especially in its handling of the Israeli ambassador.

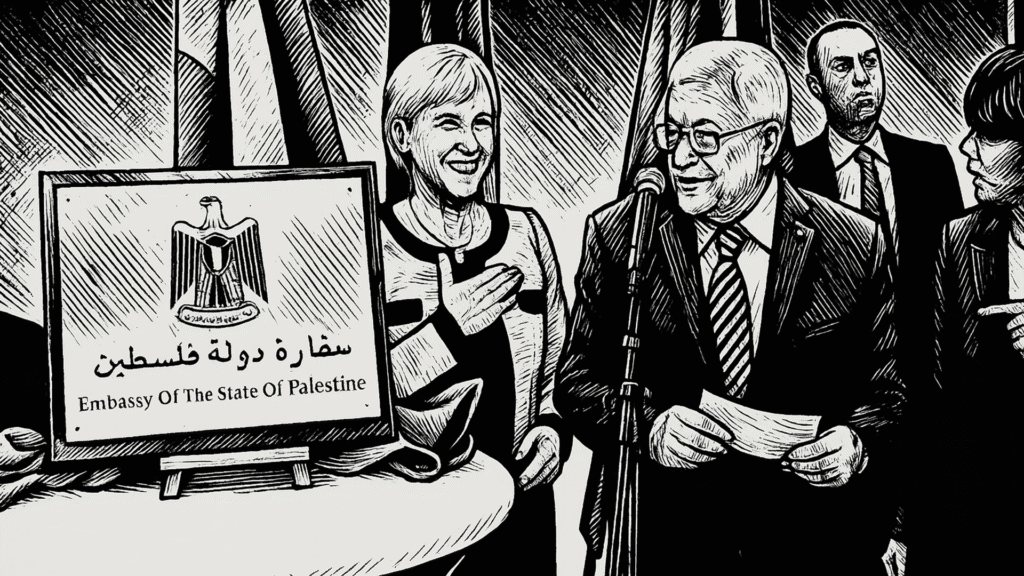

Despite this divergence, Ireland was one of the first Western countries to recognize the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). It contributed to launching the Euro-Arab dialogue, allowing the PLO to participate in the Dublin formula negotiations in 1975 and the Venice Declaration in 1980. Ireland also supported the Oslo Accords, hosted Yasser Arafat on multiple occasions, and opened a Palestinian diplomatic mission in Dublin, which later developed into a full embassy.

Nonetheless, Ireland opened an embassy in Tel Aviv in 1996. Despite this recognition, it has maintained a cautious stance toward Israel, particularly regarding settlement expansion and violations in the occupied territories. Its Catholic heritage and sensitivity toward holy sites contributed to its reluctance to grant full legal recognition to Israel until the late 20th century.

According to the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, Irish Prime Minister Éamon de Valera rejected the 1937 plan to partition Palestine. Ireland has supported UNRWA since the 1950s and increased its humanitarian aid—especially after U.S. funding cuts.

Ireland’s stance peaked recently in May 2024, when it joined Spain and Norway in officially recognizing the State of Palestine. In December of the same year, it joined South Africa’s genocide case against Israel before the International Court of Justice.

This decision, in the view of many, reflects the convergence of the Irish people’s moral conscience with a formal institutional commitment to international law and human rights.

As for immigration policy, Ireland’s official immigration website states that entering the country for work from outside the European Economic Area requires prior work permits and specific visas, which must be arranged before travel. One cannot come to Ireland for work without completing the legal procedures.

Work permits vary between short-term (such as the atypical work scheme) and long-term (such as the Critical Skills Employment Permit targeting rare professions).

There are also investment and entrepreneur programs that allow residency under specific financial conditions.

The site notes the requirement to register with immigration authorities upon arrival if staying longer than 90 days. A legal residence card is then issued according to the type of permit.

Foreigners are prohibited from working outside the terms of their permit. Violations are subject to penalties, though appeals are allowed—reflecting a precise and organized legal system for immigration and labor.

In conclusion, Ireland appears to be a serious migration option for Muslims seeking a dignified standard of living that also aligns with their political and moral convictions—especially given Ireland’s historical and current support for the Palestinian cause.

Spain

Spain is one of the leading countries in Southern Europe that combines a high quality of life, progressive social policies, and balanced positions in international politics.

According to the United Nations Development Programme’s 2023 report, Spain achieved a Human Development Index (HDI) score of 0.918, ranking 28th globally and placing it among countries with very high human development.

This progress is attributed to stable performance in health, education, and income. The average life expectancy is about 84 years, the country’s GDP exceeds $1.8 trillion, and the average annual income per capita is around $36,000.

Despite these positive indicators, the country faces economic challenges. Unemployment rates are relatively high at 11%, and major cities suffer from a severe housing crisis. Property prices have risen by 44% over the past decade, while wages have only increased by 19%, triggering notable social protests.

Nevertheless, the cost of living in Spain remains relatively low compared to other Western European countries, making it a preferred destination for many migrants and those seeking stability.

In terms of foreign policy, Spain’s position on the Palestinian cause has undergone a significant shift. As noted by Ignacio Álvarez and Osorio Alvarino in an article for the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, Madrid’s stance evolved from caution during Franco’s dictatorship to explicit support for Palestinian rights—beginning with hosting Yasser Arafat in 1979 and eventually recognizing the Palestinians’ right to an independent state.

In the 1990s, Spain played a pivotal role in sponsoring peace conferences, particularly during its presidency of the European Economic Community. It also supported the Palestinian Authority with development aid, and Spanish diplomats like Miguel Ángel Moratinos played leading roles in negotiations.

However, the events of September 11 shifted foreign policy priorities, with Prime Minister José María Aznar aligning with the United States. This translated into support for the “Road Map” conditioned on reforms within the Palestinian Authority.

When the Socialists returned to power in 2004, Spain resumed its support for the Palestinian cause—albeit cautiously—especially after Hamas won the 2006 elections. The government required recognition of Israel and a renunciation of violence. This cautious official stance, however, contrasts with strong grassroots support for Palestine, particularly evident during Israel’s attacks on Gaza in 2006 and 2008.

The 2009 amendment to Spain’s Universal Jurisdiction Law—which limited Spanish courts’ authority to investigate war crimes committed abroad—reflected the government’s desire to preserve diplomatic relations with Israel. According to an article by Hussein Majdoubi in Al-Quds Al-Arabi, this decision faced strong opposition, particularly from the Socialist Party, which threatened to challenge the law in the Supreme Court, calling it a serious step back from Spain’s international human rights commitments.

Overall, this shift reflects Spain’s attempt to avoid diplomatic clashes—even at the expense of curtailing a powerful tool of international justice once used to pursue serious human rights violators.

Within this context, the Hague Declaration of 2025, adopted by Spain, reaffirmed the illegality of annexing Palestinian land and condemned Israel’s settlement policies.

Spanish civil society has historically shown broad solidarity with the Palestinians despite the lack of a large Palestinian community in the country. Most Spaniards view Palestinians as an oppressed people struggling for their rights. This solidarity is especially strong on the political left, while right-wing parties tend to support Israel.

Civil society organizations have contributed to advocacy and awareness efforts, though often without coordination, which reduced their effectiveness. Notable initiatives include the NGO Committee on Palestine (1991), the NGO Group for Palestine (2001), and the Solidarity Network Against Israeli Occupation, which includes dozens of organizations participating in BDS campaigns and international actions.

In summary, Spanish policy toward Palestine remains a mix of symbolic political support and pragmatic economic cooperation with Israel—reflecting complex domestic and international balancing acts, even as the Palestinian cause remains central to Spanish public consciousness and a significant portion of its political and civil elite.

The greatest contradiction lies in the continued security and trade cooperation between Spain and Israel—highlighting a delicate balance between political ideals and strategic interests.

Regarding immigration, Spain has adopted, according to Secretary of State Pilar Cancela, a pioneering policy in Europe focused on legal and effective migrant integration.

Madrid launched an ambitious plan to regularize the status of 900,000 migrants by 2026, at a time when the country faces an unprecedented demographic crisis due to declining birth rates.

In a BBC Arabic article, journalist Guy Hedgecoe highlights human stories reflecting these policies—such as Michael, a Ghanaian refugee who fled violence in his homeland and arrived in the Canary Islands by boat. He now resides in a hotel in Villacilambre, which has become a reception center for around 170 asylum seekers. In 2024, Spain saw a 59% increase in arrivals compared to the previous year.

However, this surge sparked political debate, particularly from the far-right Vox party, which frames immigration as an “invasion.” Hedgecoe quotes economist Javier Díaz-Giménez, who stated that Spain will need 25 million immigrants over the next 30 years to offset the projected retirement of 14.1 million citizens in two decades.

Thousands of workers have benefited from bilateral agreements with African and Latin American countries. The May 2025 amendment to the immigration law allows migrants to regularize their status through five routes: social, professional, educational, family, and humanitarian.

The law also improved family reunification conditions and allowed students to work, though it drew criticism from rights groups for excluding asylum seekers from calculating legal residency duration and tightening reunification criteria for minors. Organizations like Caritas and the Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid challenged the law in the Supreme Court.

Regarding citizenship, the Ministry of Justice explains that naturalization generally requires 10 years of legal residence, with exceptions for certain nationalities and circumstances.

Applicants must pass Spanish language and culture tests and swear allegiance to the king and constitution.

Citizenship is also granted under the Democratic Memory Law to descendants of political exiles or victims of discriminatory laws, with applications open until October 2025. An official online portal allows applicants to track their status.

In conclusion, the Spanish experience reveals a complex model—combining economic modernity and social openness with diplomatic caution and strong grassroots solidarity.

While the state aims to promote integration and human rights, internal and external pressures continue to challenge its political and humanitarian path.

Sweden

Sweden is one of the most attractive countries for migrants worldwide—not only due to its high standard of living, but also because of its principled stances in international politics, most notably its historic support for the Palestinian cause.

Sweden is home to about 10.5 million people and ranks high globally in human development indicators.

According to the 2023 UNDP Human Development Index, Sweden scored 0.949, placing it 5th globally in the category of very high human development.

This high ranking is attributed to the country’s comprehensive public services in education, healthcare, and social welfare, as well as its high per capita income, with a net average monthly salary exceeding $3,000.

Although the cost of living is relatively high—an individual may need around $2,500 per month—the quality of life, work environment, and government attention to work-life balance make Sweden a highly attractive destination for long-term settlement.

However, as noted by the official website of the Swedish Migration Agency, since 2022 Sweden has adopted a more cautious immigration policy, focusing on attracting high-skilled workers through mechanisms like the EU Blue Card system.

Applicants for work permits must have official job offers from Swedish employers, with salaries equal to what Swedish citizens receive in the same sector.

Regarding naturalization, the Migration Agency confirms that one must reside legally and continuously in Sweden for at least five years, have a clean criminal record, good conduct, and clear identification documents to be eligible for citizenship.

Proposals have been introduced to tighten naturalization requirements, including increasing the required residency period to eight years and imposing Swedish language and civic knowledge tests. These amendments are expected to take effect in June 2026.

What distinguishes Sweden in the eyes of many Muslims is its clear stance on the Palestinian issue.

Sweden was the first major European country to officially recognize the State of Palestine in 2014. According to Dr. Mohamed Boubouch in his book The Palestinian State-Building Project: A Legal and Political Study (2015), “Sweden’s desire to recognize Palestine as a state was a positive shift from the rigid European position, which had resisted following the path of the UN General Assembly that recognized Palestine as a sovereign state in 2012.”

He adds that the recognition was not merely symbolic: “It was a parliamentary vote with an overwhelming majority—more than 274 members, with only about 12 opposing. This sparked Israeli anger and concern, as momentum for Palestinian statehood continued to grow and take root.”

Sweden has long supported the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 242, which calls for land-for-peace and the right of return for refugees. It has consistently rejected the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem.

Former Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme was one of the most prominent advocates of Palestinian self-determination. He voiced this position in international forums despite sharp Israeli criticism, remaining steadfast in his principles until his mysterious assassination in 1986.

Since the 1990s, Sweden has strongly supported the two-state solution, viewing it as the only path to lasting peace between Palestinians and Israelis. It rejected Israeli settlement activities in the occupied Palestinian territories, considering them a barrier to peace and a violation of international law, particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Despite changes in government, Sweden’s policies have maintained this direction. It has condemned excessive use of force by Israel in the Gaza wars, continued financial support for UNRWA, and refused to move its embassy to Jerusalem.

Sweden has also provided consistent support for Palestinian civil society, particularly in education, human rights, and women’s empowerment—stating that this reflects its commitment to human rights and its moral responsibility to the oppressed.

Sweden is not only a wealthy and socially advanced country—it also upholds deep humanitarian values in its political stance.

That is why it remains a preferred destination for many Muslims seeking a dignified life in a society that supports justice and defends righteous causes—chief among them the Palestinian cause.

In a world where interests compete and principles collide, migration is no longer merely a technical decision based on income and comfort—it has become a reflection of human values and a compass for one’s political and moral identity.

For many Muslims, choosing a country is not just about job security or standard of living—it’s tied to a larger question:

“Where can one live without compromising their convictions or remaining silent about just causes?”

Experiences in Malaysia, Turkey, Ireland, Spain, and Sweden show that some countries not only provide a decent life, but also offer a moral model worth emulating, especially in their stance toward Palestine—demonstrating a rare alignment between policies and principles.

These countries, despite their differences, offer Muslim migrants a chance to engage with societies that understand their causes and allow them to be active participants, not passive recipients.

As normalization increases and human rights rhetoric declines in several countries, it becomes ever more important to redefine what it means to be a host country—not just as a place to reside, but as a stance in the world.

Migration, in the end, is not merely a geographical move — it is an existential decision: Where do you stand, and with whom?