The English proverb says, “Words are like arrows: once released, they cannot be taken back.”

The Arab world was shaken—almost to the point of turmoil—following a statement by Saudi Sheikh Saleh Al-Moghamsy on That, a program broadcast by Saudi TV during Ramadan 1445 AH.

Despite his stature as the former imam and preacher of the Quba Mosque in Medina and being one of the most prominent religious figures in Saudi Arabia, he is well known through his programs, lectures, and numerous writings.

His remarks on that show stirred a storm of controversy. He openly declared his intention to establish a new Islamic legal school, saying: “The hope I ask from Allah, may He be glorified, is that He grants me the establishment of a new Islamic jurisprudential school. This is what I pray for and strive toward.”

Reactions were sharply divided. Some considered it a commendable boldness and a step toward renewing Islamic jurisprudence and liberating it from the rigidity of blind imitation.

Others saw it as a dangerous excess that compromises religious fundamentals, potentially opening the door to a “modernist Islam” that strips texts of meaning, echoing the nonsense of hostile Orientalists or the delusions of alienated liberals.

Among the strongest criticisms came from Saudi Arabia’s Council of Senior Scholars in an official press statement published by the Saudi Press Agency. The statement affirmed: “Islamic jurisprudence, with its recognised schools and diverse ijtihads, addresses all the needs of modern life and reconciles them with Islamic law. This is evidenced by scholarly bodies and fiqh councils that engage in collective ijtihad.”

The Council further added: “One of Allah’s blessings upon Muslims today is the accessibility of collective ijtihad through these bodies and councils, which respond positively to the needs of society and its intellectual, social, and economic developments. Hundreds of resolutions issued by these institutions across different fields stand as clear proof of this.”

This was not the first time Moghamsy provoked debate. In 2020, he was dismissed from his position at Quba Mosque after a tweet calling for the release of certain prisoners, interpreted as a veiled reference to detained preachers. Later, he appeared in support of events organised by the Entertainment Authority and even endorsed its chairman, Turki Al-Sheikh’s statement permitting music—even in Mecca—further fueling controversy around his persona.

To be fair, I have reflected deeply on Moghamsy’s statement, and I confess I see no issue in the emergence of a new jurisprudential school. Transactions, communications, transportation, and lifestyle in general—socially, economically, and politically—have all advanced to a level unprecedented in history.

Beyond the confinement of Islamic law to four schools—or even just two, Sunni and Shia, as many assume—Islamic thought has produced many schools, some in jurisprudence, others in theology. At times, it feels nearly impossible to enumerate them: schools of opinion, hadith, kalam, literalism (Zahiri), esotericism (Batini), and more.

Today, we even witness scholarly attempts to organise these schools and currents under the framework of maqasid (objectives of Sharia). Islamic methodologies are still evolving, and I do not believe they will ever cease to do so. The true scholars of this Ummah will continue the mission of renewal without interruption.

In an interview on Liyatafaqqahu fi al-Deen on Qaf TV, Sheikh Muhammad Al-Hasan Al-Dedew explained that madhhabs are not religion in themselves. Still, intellectual schools were established to understand the sacred texts and apply them to people’s realities. He emphasised that ijtihad was never confined to the four famous imams: according to Ibn Hazm, eighteen Companions reached the level of ijtihad, while Imam Al-Nasa’i counted twenty-two. Successive generations of followers carried this legacy forward, producing many schools in the early centuries—some vanished, leaving only traces, while others endured and spread.

These madhhabs are simply paths for understanding and applying the texts. Al-Dedew cited the Qur’anic verse in Surah al-Nisa: “If they had referred it to the Messenger and to those in authority among them, then those who can conclude it would have known it.” He explained that deriving rulings (istinbat) is the task of scholars who combine mastery of the texts, the Arabic language, and the realities of life, enabling them to address new issues and provide fatwas.

To reinforce this, Al-Dedew recalled Imam Al-Suyuti’s Al-Kawkab al-Sati‘, a didactic poem summarising Jam‘ al-Jawami‘ in Usul al-Fiqh, which listed numerous well-known mujtahids:

“Al-Shafi‘i and Malik and Al-Hanbali… Ishaq and Al-Nu‘man son of Hanbal

Ibn ‘Uyayna with Al-Thawri… Ibn Jarir with Al-Awza‘i

And the Zahiri and the rest of the imams… all guided by their Lord’s mercy.”

The Zahiri School

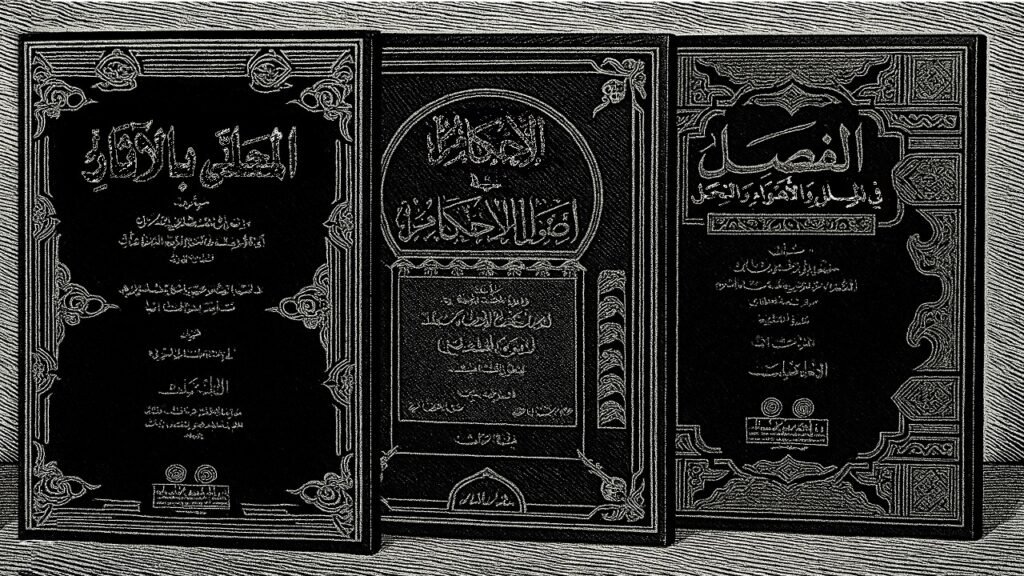

In a study on the origins of the Zahiri school, its scholars, foundations, and characteristics, conducted by Najm al-Din al-Zanki and Hasan al-Husni and published in the Journal of the University of Sharjah for Sharia and Islamic Studies, the researchers explained that the school emerged in Iraq under Imam Dawud ibn ‘Ali al-Isfahani in the 3rd century AH. He laid down its independent principles and defended them until he became known as “al-Zahiri” (the literalist).

Dawud ibn ‘Ali was influenced by Imam al-Shafi‘i in his commitment to the texts and his emphasis on them. Al-Shafi‘i interpreted the Sharia strictly based on textual evidence, but he allowed for clear and necessary analogies. Dawud, however, went a step further by rejecting analogy altogether and establishing a method that adhered strictly to the outward (literal) wording of the texts in the Arabic language—without resorting to reasoning by causes (‘illa), juristic preference (istihsan), or consideration of “public interests” (masalih mursala).

The researchers noted that the Zahiri school arose as part of an intellectual and juristic opposition movement: the “Ahl al-Ra’y” (the people of opinion) had expanded their reliance on analogy to the point where some gave it precedence over consensus, others rejected hadiths that conflicted with their analogy, and still others went so far as to reinterpret Qur’anic verses away from their intended meaning whenever these opposed their analogical reasoning or personal views.

Al-Zanki and al-Husni also mentioned another opinion which connects the rise of the Zahiri school to being the opposite pole of the esoteric (batini) movements that spread in that period, such as the Isma‘ilis and certain strands of Sufism. However, they considered this view weak, arguing that the Zahiri school was, at its core, a legal method grounded in the outward meanings of texts and their evidence. It was born out of the need to protect revelation from eccentric interpretations and excessive use of analogy. The Zahiris asserted that the Qur’an, Sunnah, and consensus were sufficient for deriving rulings, and that any expansion beyond them was a departure from the intent of the Sharia.

After Dawud, the mantle was taken up by his son Muhammad, who was regarded as a distinguished imam. Then came other scholars, such as the Iraqi jurist and prolific writer Ibn al-Mughallis, the grammarian Naftawayh, and the judge al-Khurazi, among others.

The most important role, however, was played by his student Abd Allah ibn Qasim, who met Dawud in Iraq, carried all his books with him to al-Andalus, and spread the school there. He was supported in this by Imam Baqi ibn Makhlad, one of the most outstanding hadith scholars of the time and a staunch advocate of adhering to the Sunnah and the traditions.

During the reign of ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Nasir, the eighth ruler of the Umayyad dynasty in al-Andalus, the judge Mundhir ibn Sa‘id al-Balluti played a significant role in consolidating the Zahiri school thanks to his knowledge and his judicial authority. Later, Abu al-Khiyar Mas‘ud ibn Muflit, the teacher of Ibn Hazm, carried the school forward.

Finally, it was Imam Ibn Hazm of al-Andalus who revived the Zahiri school. He immersed himself in the writings of Dawud, which were well known in al-Andalus, and expanded and developed them in his own works. Through his debates, polemics, and prolific writings, Ibn Hazm breathed new life into the Zahiri school, establishing it as a distinct and enduring school of Islamic jurisprudence that could not be overlooked in the history of Islamic law.

Ibn Hazm of al-Andalus

He is ʿAli ibn Ahmad ibn Saʿid ibn Hazm al-Andalusi al-Qurtubi, whose lineage traces back to Sufyan ibn Yazid. Born in 384 AH, Ibn Hazm is regarded as one of the most outstanding scholars of al-Andalus and among the most prolific authors in the history of Islam after al-Tabari.

He was also a man of letters, a poet, a genealogist, and an expert in the study of hadith transmitters. Briefly, he held ministerial posts under three caliphs: al-Murtada in Valencia, his friend ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Mustazhir Billah, and Hisham al-Muʿtadd, the last caliph of Cordoba and the final ruler of the Umayyad dynasty in al-Andalus.

Ibn Hazm’s intellectual legacy was not the product of chance or scattered effort, but the result of a deliberate plan and a precise methodology he set for himself from the outset. He knew his path well, where to begin and where he wished to end. His writings were consistently directed toward serving his Zahiri convictions, organised within a coherent framework that gave his thought the structure of a unified system.

What distinguishes his work is not only the abundance of material but the manner in which he articulated his ideas: with orderly presentation, captivating clarity, and a vision marked by rigour and consistency. It is difficult to find another thinker who managed to formulate his intellectual project with such discipline.

Anwar al-Zuʿbi, in his book The Zahiri Approach of Ibn Hazm of al-Andalus: Epistemology and Methods of Inquiry (2008) notes that Ibn Hazm’s orientation was also reflected in his personal life. His withdrawal from politics was not an abandonment of public affairs, but rather a reflection of harmony with his school of thought, which emphasised congruence between inward and outward states.

Al-Zuʿbi notes that the political climate at the end of the Umayyad caliphate was marked by intrigue and manipulation, prompting many to conceal their true beliefs. This clashed with the Zahiri vision of integrity in both word and deed, in both private and public settings. Thus, Ibn Hazm sought refuge in scholarship and research, where he could attain the sincerity he yearned for.

His books were burned in Seville in 448 AH due to sectarian and political tensions of the time. According to Dr. Sulayman al-Bayadi in his article The Calamity of Ibn Hazm: The Journey of Andalusia’s Encyclopedic Scholar from Losing Ministry to the Burning of His Books, published in Bawabat al-Ahram, Ibn Hazm was bold in expressing his views without embellishment, confronting Maliki jurists with severe criticism. This aroused the resentment of both scholars and rulers.

Efforts converged to silence him, culminating in a decree to publicly burn his works in Seville, under the pretext of defending the Maliki school and halting what some considered a dangerous innovation.

Yet, despite this widespread campaign, Ibn Hazm’s intellectual legacy endured. His students preserved and transmitted his writings, which later totalled around 80,000 folios. This proves that the burning of his books failed to erase his thought, whose light continued to shine across the centuries.

Ibn Hazm’s Zahiri Method

By its very nature, Zahiri thought is rooted in dealing with the outward meanings of words and matters, reducing them to rational axioms and sensory realities, as al-Zuʿbi describes. Whatever had no basis in reason, perception, or explicit text was deemed idle and unworthy of consideration.

This led to Ibn Hazm’s sharpness and seriousness in debate. He pursued his opponents relentlessly, attacking what he considered innovations or transgressions unsupported by valid evidence. This intellectual rigour earned him great respect among his contemporaries, even if they criticised his severity and lack of flexibility in politics and disputation.

Ibn Hazm made scholarship the central domain of his life. He turned away from positions of power and intrigue, dedicating himself to study and authorship. He drew on his earlier observations, criticisms, and debates, employing his literary and poetic skills in the service of his project.

Thus, his character took shape as a Zahiri jurist deeply faithful to the revealed texts of Qur’an and Sunnah, and as a rational thinker of uncompromising strictness, unwilling to allow anyone to overstep the bounds of reason and sense without decisive proof.

He built his methodology on categorical principles that did not lend themselves to interpretation. As long as a text remained, its ruling could not be revoked except by another text of equal authority. This was known as istishab (presumption of continuity): anything without explicit textual evidence remained permissible.

Ibn Hazm relied on istishab in multiple forms, laying the groundwork for a rigorous, text-centred approach. First, he maintained the generality of a text unless a specific exception appeared. For instance, he allowed the sacrifice of any edible animal—horse, camel, wild ox, or rooster—citing the Qur’anic verse in Surah al-Hajj: “And do good that you may succeed.”

He also emphasised specificity: rulings applied only to what the text explicitly mentioned. Thus, he limited the prohibition of unequal exchange to wheat alone, not other grains, and confined the ruling of spoilt clarified butter by a dead mouse to butter itself, not to other liquids.

For him, the default ruling on things was permissibility unless prohibited by text, citing the verse: “It is He who created for you all that is on earth” (2:29).

Moreover, istishab was always tied to certainty: certainty could never be removed by doubt. He cited the hadith narrated by Ibn ʿAbbas in which the Prophet ﷺ said: “Satan comes to one of you in prayer and blows into his seat, making him imagine that he has broken wind when he has not. If this happens, he should not leave his prayer until he hears a sound or detects a smell.”

Finally, he upheld the principle of original non-existence: the human conscience is free of obligations, conditions, or commitments except those proven by text or consensus. Thus, istishab became for him a safeguard against innovation, ensuring that no rulings existed without specific textual evidence.

He also rejected reliance on dalīl al-khitāb (argument from implied meaning)—that is, inferring from the mention of something that the ruling applies in the opposite sense to what is left unmentioned, so that the unspoken carries the opposite ruling of the stated. As ʿIyāḍ al-Sulami defined it in his book Usūl al-Fiqh All Jurists Must Not Be Ignorant Of (2019), Ibn Hazm regarded this as artificial and invalid. He held that the legal terms of revelation remain general in scope unless sound evidence restricts them.

Examples of this method include the Prophet’s ﷺ response to the woman who asked whether women must perform ghusl if they experience a dream. He said, “Yes, if she sees discharge.” Some jurists used this to argue that the absence of discharge negates the requirement of ghusl. Others inferred from the Qur’anic verse “Flog them with eighty lashes” (24:4) that neither fewer nor more lashes are allowed. Likewise, the hadith “There is no zakat on wealth until a year passes over it” was taken to mean that zakat becomes obligatory upon completion of a year. The verse “Complete the fast until the night” (2:187) was taken to prohibit fasting at night. Ibn Hazm rejected such reasoning as an invalid extension.

He also held that the Prophet’s ﷺ actions were not obligatory unless they clarified a command; otherwise, they were recommended but not binding. He denied the permissibility of following the laws of earlier prophets after Muhammad ﷺ, citing the verse: “For each of you We have made a law and a way. If Allah had willed, He would have made you one community” (5:48).

Lastly, Ibn Hazm and those who followed his Zahiri methodology categorically rejected blind imitation (taqlid). No Muslim, he argued, may adopt another’s opinion without evidence that convinces him personally—even if the source were a Companion. He even maintained that a mistaken mujtahid is better before God than a correct imitator. Yet he continued to revere the great imams of the schools, seeing disagreement with them not as disparagement of their rank, but as legitimate divergence in opinion.

Rejection of Imitation in the Zahiri School

Many believe that the Zahiri school is nothing more than a handful of Ibn Hazm’s writings, that it has no scholars and no continuation beyond his legacy. Hence, the need for clarification: Zahiri’s thought is not merely a “madhhab” (school), but a methodology and approach to engaging with the sacred texts and reasoning from them.

Ibn Hazm expressed this in his book al-Ihkam, stating: “The outward (zahir) is the text itself.” Thus, adherence to the apparent wording became the very essence of the method. For this reason, it may rightly be called the “Zahiri school” or the “Zahiri methodology.” The difference is that a school can invite blind following (taqlid), whereas a methodology recognises only recourse to the texts. For that reason, some scholars preferred to describe it as a methodology.

Scholars explained that a follower within a school is nothing more than a “restricted jurist” (mujtahid muqayyad), orbiting within the sphere of his teacher.

But whoever breaks free from the chains of imitation and returns to the texts themselves, guided directly by them—as Ibn Hazm, Ibn Taymiyya, and al-ʿIzz ibn ʿAbd al-Salam did—becomes an absolute jurist (mujtahid mutlaq). Such a scholar selects from the schools the strongest opinions in his view, supported by evidence and proof. Their position may be compared to that of a sharp-eyed bird soaring freely across a vast horizon.

No one claims that Ibn Hazm, Dawud, or any other Zahiri scholar was infallible. Their words cannot be treated as sacred law to be followed blindly. That would be blind imitation itself, the very error into which the imitators of other schools have fallen.

If, however, engagement with their writings consists of weighing their arguments against the texts and evaluating them critically, then this constitutes the true madhhab and the sound methodology.

It is to the credit of all the great imams that they agreed upon a golden rule, summarised by Imam al-Shafiʿi in his saying: “If the hadith is authentic, then it is my madhhab.” None of them ever consented to being followed blindly in ways that contradicted the revealed texts.

Thus, it is essential to distinguish between the terms “madhhab” and “manhaj.” A madhhab, in the jurists’ usage, is a single path trodden by followers of an imam, shadowing him wherever he turns. But a manhaj is much broader, branching into multiple paths according to the variety of texts and their meanings.

This is why, within each madhhab, we find sub-schools attributed to its outstanding figures. Among the Malikis, for instance, there were the schools of the Egyptian jurist ʿAbd Allah ibn ʿAbd al-Hakam and that of ʿAbd al-Rahman ibn al-Qasim, Malik’s longest-serving student, as well as others.

In conclusion, the manhaj is broader and sounder in use than the madhhab. It frees the researcher from the narrow confines of dependency on a single interpretation and opens up the vast space of the texts themselves, with their inherent richness and flexibility.

Even if we were to use the term madhhabiyya (school-based adherence) to mean the spirit of renewal grounded in ijtihad, we would not be mistaken. We would, in fact, be following in the footsteps of Imam Ibn Hazm himself, who had already adopted this path—reviving the spirit of independent reasoning and tying it firmly to the authority of the sacred text.