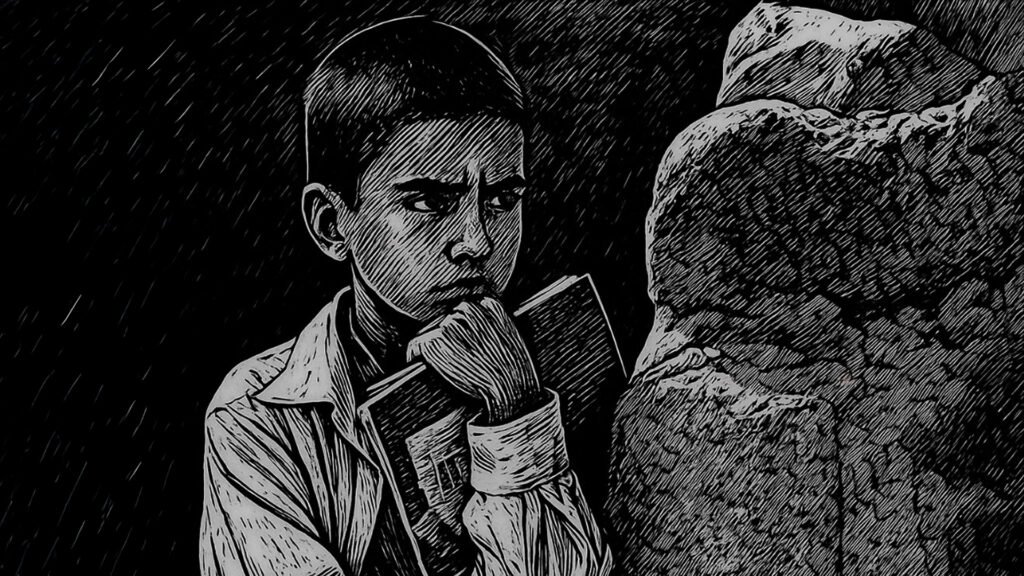

When we hear the phrase child labor, the immediate image that comes to mind is that of a miserable child toiling in a dark factory or a dust-filled mine, shocking the world with his frailty as he carries weights far beyond his strength. This tragic, painful image prompts us to raise our voices in rejection, demand laws and criminalization, and feel a moral comfort that we have done our duty.

But if we look a little deeper, and strip away the glittering headlines and official statements, we will discover that the phenomenon is far more complex. We will find other faces of child labor, faces that do not resemble those of the vulnerable children in mines or factories, yet are no less filled with misery and sorrow.

Take, for example, a young player on a junior team, a talented girl in a ballet troupe, or a boy training at a music academy. They undergo near-military regimens of daily training that last for long hours, stolen from their education, their playtime, and their simple dreams.

We applaud them when they achieve victories and celebrate their triumphs on stage, yet we turn a blind eye to the heavy price: an exhausted body, a stolen childhood, and a psyche weighed down by stress and pressures.

This paradox exposes the duplicity in our stance: we reject child labor in a coal mine, yet we cheer for the little girl whose feet bleed from dance training, or the boy who struggles at school because he spends his nights in sports drills.

What is striking is that those who call for an absolute ban on child labor at the same time readily accept the strict involvement of children in sports and arts from an early age, with grueling training, intense psychological pressure, and near-military discipline—not for the sake of play and fun, but to achieve high rankings, professionalism, and financial gain. This often negatively affects their academic performance.

So why do these same people see no problem with the pressures children face during their engagement in such sports or artistic activities, while they demand a total ban on child labor on the grounds of preserving childhood and not disrupting educational pathways?

And is traditional education, which focuses on certain intellectual skills while neglecting others, truly the best option for a child’s growth and preparation for the future?

In an article titled Grin and bear it in the British newspaper The Independent, Belarusian gymnastics icon Olga Korbut—who represented the Soviet Union at the 1972 Munich Olympics at the age of seventeen—said that her coach Renald Knysh “before the 1972 Munich Olympics, where she won three gold medals as a teenager, forced her to have sex with him after carefully slipping her some cheap cognac.”

She also told a Russian newspaper that “Knysh, along with other Soviet coaches, did not see their gymnasts as merely potential athletes, but as future concubines.” She accused him of beating her and attempting to control every aspect of her life, fearing that any relationship with young men would distract her from sport.

According to her, “her harsh coach even invented daring moves for her, such as the Korbut Flip, where she had to hurl herself backward off the high bar to catch it again. It took five years and three concussions before she mastered it.”

Richard Anker, in a study entitled The Economics of Child Labor: A Framework for Measurement examines the phenomenon of child labor from an economic perspective, seeking to understand it more deeply and comprehensively. He argues that settling for the simplistic view that regards child labor as pure evil overlooks the complex social and economic realities that drive children into work.

From this standpoint, the researcher stresses the need for a precise approach to measurement, differentiating between various forms of labor, and then proposes more effective policies to reduce the harmful aspects of child labor.

The study identifies three main dimensions of child labor. The first is child protection, since childhood is a fragile stage that requires special safeguards from hazardous or exploitative work. The Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention (1999, No. 182) reflected this global consensus.

The second dimension focuses on child development, as excessive work often conflicts with education and academic performance. Although some forms of light work may provide children with life skills such as self-reliance and valuable social experiences, once work exceeds certain limits (e.g., 15 hours a week), it tends to show negative effects on schooling.

The third dimension concerns the economic and labor market impacts. At the micro level, children’s earnings represent a survival factor for poor families. At the macro level, however, child labor contributes to lowering adult wages and increasing unemployment rates among them, thereby perpetuating intergenerational poverty.

By contrast, investment in education paves the way for a developmental cycle that fosters higher productivity, improved health outcomes, and broader social equity.

The researcher then turns to the challenges of definition and measurement. Aggregate figures on child labor vary greatly. For example, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated in 1995 that there were 73 million working children aged 10 to 14. A year later, in 1996, the figure jumped to 250 million children aged 5 to 14. This leap in statistics was due to weak data and inconsistent standards.

Anker therefore emphasizes that a single number is insufficient, as it conflates very different types of work—from light to hazardous, paid to unpaid, and compatible with schooling to disruptive of it. What is needed are multiple indicators that distinguish between acceptable and harmful forms of child labor.

This was also reflected in ILO conventions, such as the Minimum Age Convention (No. 138/1973), which set minimum ages for employment in developing countries or for light work, and the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention (No. 182/1999), which prohibited slavery, sexual exploitation, criminal activities, and work hazardous to health or morals.

At the detailed measurement level, the researcher explains that the definition of economic activity under the System of National Accounts is very broad and even includes work on family farms for self-consumption. This means that children in rural areas are heavily counted within this broad definition.

The main difficulty, however, lies in measuring hazardous work due to its secretive nature, since it is illegal. Therefore, the researcher suggests rapid statistical surveys or relying on local experts to identify hazardous tasks, in addition to asking direct questions about injuries and levels of exposure to occupational risks.

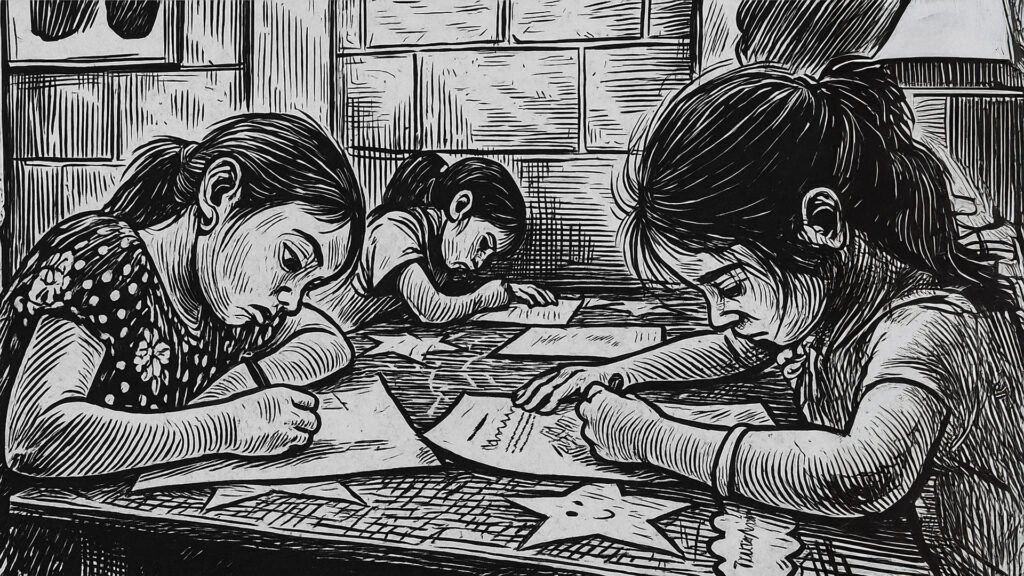

He also discusses the relationship between education and work, noting that a child’s presence in school does not necessarily mean actual learning. Many children attend school but leave nearly illiterate because of poor education quality, and schools themselves can sometimes be environments of abuse due to violence, overcrowding, or corporal punishment.

He further points out that combining study and work is common. In Ghana, for example, half of the students work, and 70% of working children also attend school. Even in developed countries, some children work after the school day or during holidays. Hence, the optimal policy is to organize school schedules in line with agricultural seasons and adapt curricula to include practical skills.

Anker adds that domestic work and childcare, although not officially counted as labor, place a particular burden on girls and hinder their education. Therefore, they should be included in analyses.

From a policy perspective, the researcher argues for a dual approach: on one hand, launching special programs aimed at eliminating the worst forms of labor—hazardous and exploitative work—and on the other, integrating non-hazardous tasks into education, poverty reduction, and social development policies.

For these programs to succeed, strict legal protections must be provided, along with economic incentives such as financial support for poor families, alternative job opportunities for adults, and improvements in education quality as the only convincing alternative to work. In addition, awareness campaigns and cooperation with employers and community leaders are essential to changing traditional norms. The researcher stresses that accurate knowledge and reliable data are critical for guiding policies, especially in estimating the scale of hazardous work.

In short, the researcher concludes that child labor is not a single, uniform phenomenon: some forms are destructive and must be eradicated immediately, while others may be acceptable if they do not harm health or education. Successful policy is that which takes into account family poverty, the quality of education, and the context of the labor market. In this way, the issue of child labor shifts from being merely a moral slogan to a development strategy to combat poverty and build human capital that fosters sustainable economic growth.

In another study entitled Child Labor from an Islamic Perspective, researchers Abu Talib Muhammad Manwar of the University of Malaya in Malaysia and Dewan Mahbub Hossain of the University of Dhaka in Bangladesh sought to derive the Islamic view of child labor by returning to the Qur’an, the Sunnah of the Prophet ﷺ, and the writings of jurists and Muslim thinkers.

The researchers show that child labor has become a complex global phenomenon, shaped by economic, social, and cultural dimensions. While human rights organizations view it as a blatant violation of children’s rights, many poor families see it as a means of survival and securing a minimum level of income.

Here arises a central question: Can Islam provide a balanced framework that protects children’s rights while also addressing economic and social necessities?

The study reviews the literature on child labor worldwide. Poverty is the most prominent driver pushing families to send their children to work, followed by weak educational infrastructure and lack of schools or their remoteness from rural areas, and then the exploitation by employers of the cheap wages of children. In addition, social traditions in some societies reinforce the idea that a child should contribute to the family income early on.

Against these realities, Islam offers a bright picture of the child’s status and rights. The Qur’an and Sunnah guarantee a child the right to life from the moment he or she is a fetus in the mother’s womb, prohibiting abortion except in extreme necessity. The child also has the right to lineage, inheritance, healthcare, proper nutrition, education, and moral upbringing. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ himself was an example of mercy with children: he played with them, treated them kindly, and shortened congregational prayers out of compassion for a crying infant.

As narrated by Al-Bukhari and Muslim from Abu Huraira: “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ kissed Al-Hasan ibn ‘Ali. Al-Aqra‘ ibn Habis said, ‘I have ten children, and I have never kissed any of them.’ The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, ‘Whoever does not show mercy will not be shown mercy.’”

All this indicates that Islam places the child in a position of dignity and care, granting rights that must not be violated.

At the same time, Islam places high value on work, considering it a form of worship and a means of drawing closer to God—provided it is legitimate and free of injustice. The sacred texts stipulate that wages must be paid without delay, and that no worker may be burdened beyond their capacity. Islam also calls for balancing the duties and rights of the worker, and the interests of the employer with the dignity of the laborer.

But the question remains: how does this apply to children?

The study distinguishes between several concepts. The first is exploitative labor, which involves using children in strenuous, hazardous, or harmful work that damages their health, psychology, or education. Islam prohibits this type of child labor, as it falls under the principle of “no harm and no reciprocating harm.”

The second concept is beneficial educational labor, which refers to assigning tasks to a child that help develop skills or provide reasonable income without exposing the child to harm or depriving them of education—for example, helping in the family shop after school or learning light craft skills. This type is permissible and even encouraged as a form of practical upbringing.

The third concept is that of service or simple tasks performed by a child in his natural environment, such as helping parents with household chores or running small errands. This is permissible under Islamic law and is considered part of upbringing and fostering a sense of responsibility.

A prominent example is the service of the noble Companion Anas ibn Malik to the Prophet ﷺ for nine years. It is known that the Prophet assigned him only simple tasks, such as carrying water, a staff, or a miswak, and never burdened him with anything exhausting or scolded him if he fell short. Rather, the Prophet addressed him with affectionate diminutives like Anays or Bunayy, and treated him like a son. This model shows how a child’s work can serve as a means of education, training, and gaining experience, not as a tool of exploitation.

By examining the texts and scholarly opinions, clear guidelines can be derived: the work must not be in a prohibited or immoral field; it must not exceed the child’s physical capacity or endanger their health; it must not deprive them of education or hinder their intellectual or psychological growth. Parental approval is required since they are responsible for the child’s care. The work must also be defined in terms of tasks, time, and compensation, while respecting the child’s right to play and recreation essential for psychological and physical growth. The child must be treated with mercy and kindness, not harshness or violence.

The study argues that addressing the phenomenon should not be limited to the state alone but should take place on four interconnected levels. At the individual level, the child should learn Islamic values from an early age to distinguish between what is beneficial and what is harmful, so as not to be drawn into work that harms their faith or health.

At the family level, parents bear the responsibility of protecting their children, providing for their needs as much as possible, ensuring their education, and raising them ethically, while balancing material needs with the child’s rights.

At the institutional or workplace level, employers are responsible for adhering to principles of benevolence and mercy, avoiding exploitation of children’s needs, and providing a safe environment that emphasizes education rather than exhaustion.

At the political level, the state must enact laws rooted in the objectives of Islamic law (Maqasid al-Sharia) that protect the child, such as the principle “harm must be eliminated.” It must also address the root causes of child labor—poverty, unemployment, and weak education—rather than settling for a superficial ban.

What distinguishes the Islamic perspective is that it does not stop at laws or material aspects but adds a spiritual and ethical dimension. Treating children with mercy and benevolence is part of worship, and working for their best interest is not only a social duty but also a means of attaining God’s pleasure. This dimension makes the Islamic view more comprehensive, combining pragmatic and faith-based motives.

Despite the clarity of the Islamic vision, implementation remains difficult in many Muslim countries due to poverty, unemployment, and weak education. Impoverished families may be forced to send their children to work even if they know it does not align with Islamic teachings. Therefore, the study recommends focusing on eliminating hazardous child labor rather than unrealistically aiming to eradicate all forms. In other words, the goal is to protect the child from exploitation and harm, not to deprive them of all useful practical experience.

The study concludes that the Islamic position does not differ much from the contemporary international stance: Islam prohibits hazardous and exploitative child labor, but it does not forbid children’s participation in light, beneficial tasks that teach responsibility and help support poor families—provided these do not conflict with education, health, or dignity. This reflects a balanced perspective on child labor, avoiding both excess that allows all forms of labor and neglect that bans all work outright.

In a critical look at prevailing education systems worldwide, Sir Ken Robinson, in his TED talk Do Schools Kill Creativity?, stresses that risk-taking is the key to effective education that leaves a positive impact on learners. Children by nature are not afraid of making mistakes; they experiment, fail, and try again. But over time, under rigid education systems, this boldness shrinks. Adults, on the other hand, grow fearful of being wrong, and schools and workplaces are run with a punitive spirit that criminalizes mistakes. The result is that people grow up having lost their creative capacity, no longer willing to take risks.

Robinson cites a remark by the Spanish artist Pablo Picasso: “All children are born artists. The problem is how to remain an artist as we grow up.” This captures the core idea—traditional education does not expand creativity, but rather narrows it until it extinguishes it.

Robinson observes that nearly all education systems worldwide share the same hierarchy: mathematics and languages at the top, followed by the humanities, with the arts at the bottom. Even within the arts, music and visual arts are prioritized over drama and dance. This hierarchy is global and not coincidental—it emerged in the nineteenth century to meet the needs of the industrial revolution.

The aim back then was to produce a qualified workforce, which is why subjects tied to work and production were valued, while artistic talents such as playing music, painting, or dancing were neglected as they were seen as not leading to jobs. As a result, millions of children were deprived of nurturing their talents because schools pushed them away from these pursuits, arguing that they “would not find work in that field.”

Today, however, the world has changed drastically. The future can no longer be confined to traditional industries or old classifications of professions. The digital and technological revolution has reshaped the labor market. Yet education remains captive to this outdated hierarchical structure.

Robinson asks: if we looked at public education from the outside and asked about its ultimate purpose, the answer would simply be to produce university professors. The entire system appears as a long channel culminating in academia, where the highest value is placed on pure academic ability.

But this framework is unfair to millions of talented individuals who do not fit traditional academic standards. Many who possess great talent in art, kinesthetic thinking, or practical innovation were labeled as failures in school because they did not excel academically. Consequently, their intelligence was unrecognized, their creativity undeveloped, and they left the system convinced of their lesser worth.

Today, we witness what Robinson calls academic inflation. In the past, a university degree opened the doors to employment. Now, it barely qualifies you to stand in line. A master’s degree is required where once a bachelor’s sufficed; a doctorate is demanded where a master’s used to be enough. Millions of young people graduate every year, yet remain unemployed because the job market has shifted dramatically. This quantitative explosion has devalued academic qualifications and proven that tying education exclusively to academic ability is no longer viable.

Robinson argues that rethinking education requires rethinking the very concept of intelligence. Intelligence is diverse, encompassing not only logical-linguistic thinking but also visual, kinesthetic, musical, social, and emotional modes. We think with our bodies as well as our minds.

Intelligence is also dynamic, often arising from the interaction of different modes of thought—the brain is not divided into isolated compartments but functions as an integrated whole.

And it is unique, as every person has their own way of thinking and expressing themselves; what works for one may not work for another.

One of Robinson’s most powerful stories is that of Gillian Lynne, the famed choreographer behind musicals such as Cats and The Phantom of the Opera. As a child, she was labeled as a poor student and restless. Her school suspected she had a learning disorder, so her parents took her to a specialist. The doctor noticed something important: when left alone with music, she moved her body in harmony as if she were thinking through movement. He realized she was not sick but naturally gifted with kinesthetic intelligence. That was the start of her artistic journey. This story captures Robinson’s central message: talents do not disappear—they are wasted because we fail to recognize them.

Robinson concludes that our current education system is no longer fit for our era. It was designed for the age of the industrial revolution, while we now live in an age of knowledge and technology. Continuing to educate children in the same way condemns entire generations to be unprepared for the future.

Therefore, we need an educational revolution, not superficial reforms—a revolution that recognizes education as a rich environment enabling every child to discover their unique talents, rather than just a pipeline to produce workers and professors.

Robinson reminds us that education is not merely a technical responsibility but a moral and human responsibility. Today’s children will live to see the future we may never reach. Our mission is not to prepare them for our present, but to help them build their future, to preserve the richness of their creative energy, not extinguish it through fear of mistakes, rigid curricula, or exclusion from academic elitism.

If we truly wish to build a better world, we must redefine childhood. Childhood is not a stage to be shielded from all practical experience, nor is it a period to be drained in the name of achievement or profit. It is a stage for planting potential.

When we provide children with a balanced environment that protects them from exploitation and opens doors to learning, play, and creativity, we are not only protecting them but investing in the future of humanity as a whole.

When we hear the phrase child labor, the immediate image that comes to mind is that of a miserable child toiling in a dark factory or a dust-filled mine, shocking the world with his frailty as he carries weights far beyond his strength. This tragic, painful image prompts us to raise our voices in rejection, demand laws and criminalization, and feel a moral comfort that we have done our duty.

Children are a trust that we must protect.

Departement of Sharia

Departamento de Sharia

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs-ar/

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/

When we hear the phrase child labor, the immediate image that comes to mind is that of a miserable child toiling in a dark factory or a dust-filled mine, shocking the world with his frailty as he carries weights far beyond his strength. This tragic, painful image prompts us to raise our voices in rejection, demand laws and criminalization, and feel a moral comfort that we have done our duty.

Children are a trust that we must protect.

Departement of Sharia

Departamento de Sharia

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs-ar/

https://www.univ-msila.dz/site/shs/