We stand before a maritime story no less thrilling than great adventure novels, yet this time it is no fiction, but an international reality shaped by a quiet yet profoundly influential UN body—the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Founded in 1948 under the name Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization (IMCO), it has become the cornerstone of building a global legal system for maritime navigation, one of the most complex transport networks on Earth.

The concept of maritime navigation is confined “to the sea within its scientific and geographical boundaries, through ships that meet the conditions and specifications enabling them to withstand marine risks,” as stated by Faiz Thanoon in his book Principles of Maritime Law (2017).

Since humanity first took to the seas, it has discovered their immense importance as pathways connecting continents. They soon became vital routes for communication between nations. Old colonial powers exploited the seas to expand their interests, colonizing lands through fleets that roamed the oceans.

Yet the seas are not only used as routes of conquest, but also as arteries of commercial navigation, carrying goods from one country to another. Today, maritime transport accounts for a major share of international trade exchanges. Beyond transport, the seas hold other undeniable importance in their living and mineral wealth.

Thanoon divides navigation into four main types. By importance: principal navigation, which includes transporting people, goods, fishing, or leisure, and auxiliary navigation, such as rescue, pilotage, and towing vessels—both subject to maritime law.

By distance: coastal navigation, which takes place between national ports—either on one sea (minor coastal) or across two different seas (major coastal)—and high seas navigation, conducted between national and foreign ports. Coastal navigation is reserved exclusively for national vessels.

By purpose: commercial navigation for profit through cargo and passenger transport; fishing navigation for marine resources; and leisure navigation, including yachts and research vessels—all under maritime law, given their exposure to sea risks.

Finally, by ownership: private navigation carried out by individuals or companies, and public navigation by state vessels, such as warships, research, and public service ships. The latter enjoy special judicial immunity under the 1926 Brussels Convention.

The Brussels Convention of 1926 set unified rules for maritime mortgages and privileges, giving international validity to registered mortgages, prioritizing debts like port fees, crew wages, and compensation. Privileges usually expire after a year but follow the vessel even under new ownership, with exceptions for warships and some national law discretion.

But international conventions began earlier, spurred by the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, which revealed the fragility of maritime safety standards. This tragedy led to the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in 1914, which has evolved into a living maritime constitution, constantly updated to cover everything from ship construction to life-saving appliances and fire protection.

The major turning point came with the Torrey Canyon oil tanker disaster of 1967, when thousands of tons of oil spilled along Britain’s Cornish coast, polluting the sea and exposing a grave legal gap in compensation and liability. This brought marine environmental protection into the IMO’s core mission, leading to the establishment of the Marine Environment Protection Committee alongside the Safety Committee.

Then came the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs) in 1972, which created the equivalent of maritime highways. It introduced traffic separation schemes in congested straits like the Dover Strait, as well as rules for determining safe speeds and crossing safely. The results were dramatic: collisions dropped significantly, and what had been chaos was transformed into a strict order resembling the discipline of land roads.

The COLREGs comprise 41 rules divided into six sections and four annexes, covering ship conduct, lights, signals, and compliance mechanisms, all applied globally to ensure safe navigation and prevent collisions. The regulations modernized old maritime rules and made traffic separation systems mandatory to reduce accidents.

The IMO’s efforts also extended to saving lives through the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR), which established coordinated rescue centers operating around the clock and allowed for cross-border regional intervention in cases of danger to life.

This Convention created a global rescue plan through regional coordination centers. It was amended in 1998 to strengthen regional cooperation and integration between maritime and aeronautical services, with 2004 amendments ensuring that survivors are taken to a place of safety.

The IMO also turned its attention to fighting piracy and terrorism through the 1988 Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation (SUA), with additional protocols adopted in 2005 to cover new threats.

This Convention addressed crimes such as ship hijackings and violence against crews and passengers, obliging states to prosecute or extradite offenders. The 2005 Protocols expanded the scope of offenses to include biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons, environmental pollution, and the illegal transport of hazardous materials. They also introduced provisions on extradition, international cooperation, ship and platform inspections, while ensuring respect for human dignity and human rights.

Looking closely at global campaigns against pollution, one sees a real environmental threat that has reached advanced stages, despite the adoption of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) in 1973. MARPOL includes six technical annexes: oil pollution, control of harmful liquid substances, packaged harmful materials, sewage, garbage, and air pollution. It also designates special areas with strict discharge rules.

Measures include requiring tankers to have double hulls, banning the discharge of harmful substances near coasts, prohibiting plastics from being dumped at sea, and regulating sulphur and nitrogen emissions. In 2011, a new chapter was added to improve energy efficiency and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, making MARPOL a cornerstone for protecting the oceans and the global climate.

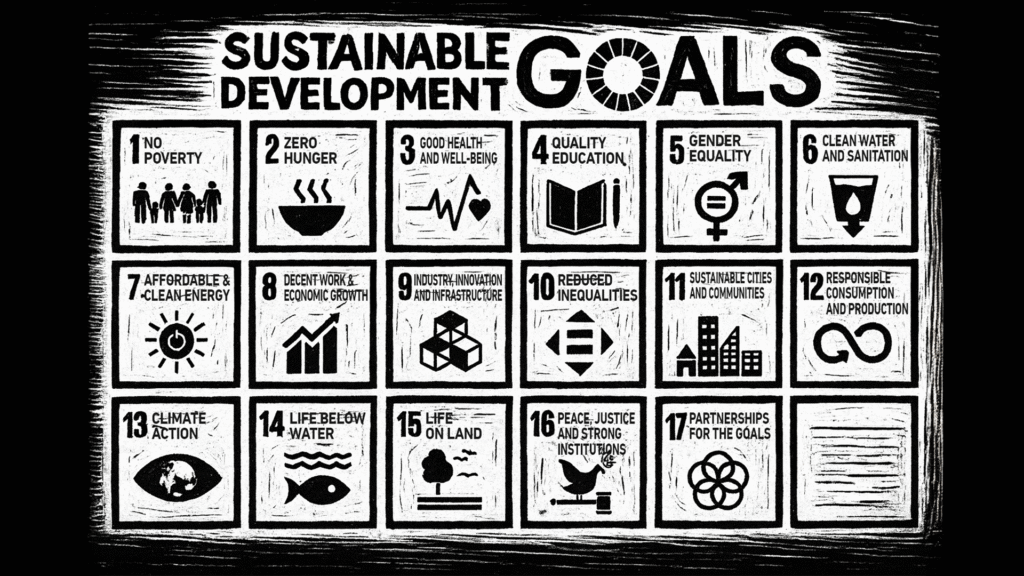

Overall, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) seeks to promote sustainable development through multiple avenues. Looking at the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, there is clear alignment between these goals, the IMO, and the shipping sector. The connection is especially strong with Goal 14 on “Life Below Water,” which focuses on conserving and sustainably using marine resources.

The issue also ties into Goal 13 on climate action, Goal 9 on industry, innovation and infrastructure, and Goal 17 on building partnerships to achieve the goals.

The adoption of the IMO’s new greenhouse gas emissions strategy in 2023 marked a pivotal step toward achieving carbon neutrality in the shipping industry by around mid-century.

Equally important is the Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks, which obliges shipowners to bear the costs of removing wrecks, including sunken containers. The IMO also prepared for the issue of ship recycling through the Hong Kong Convention, which entered into force in June 2025, requiring hazardous materials inventories and safety plans to protect workers and the environment at dismantling yards.

To achieve Nairobi’s objectives, the convention set provisions on reporting ships and wrecks, locating them, and assessing the risks they pose, including damage to the marine environment.

It also specifies measures to facilitate wreck removal and holds shipowners liable for costs of locating, marking, and removing wrecks. Registered shipowners are required to maintain compulsory insurance or other financial security to cover such liabilities.

Recognizing that accidents can never be fully prevented, the IMO established a financial compensation system through the 1969 International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage and its 1992 Protocol. These instruments ensure compensation for those affected by oil spills from ships, placing direct liability on shipowners, who are required to carry insurance or financial guarantees, with liability limits based on ship tonnage.

The 1992 Protocol expanded the convention’s scope to cover the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), authorized compensation for costs of restoring polluted environments, and recognized preventive measures even where no spill occurred. It also removed the right of shipowners to limit liability in cases of gross negligence or intentional acts.

The 2000 Amendments raised compensation limits by 50%. For ships not exceeding 5,000 gross tons, liability is capped at 4.51 million Special Drawing Rights (SDR) (around US$5.78 million).

For ships between 5,000 and 140,000 gross tons, liability is set at 4.51 million SDR plus 631 SDR for each ton over 5,000.

For ships above 140,000 gross tons, liability is capped at 89.77 million SDR. These revisions made the system more equitable and better suited to address environmental and economic damage caused by oil pollution incidents.

This system guarantees compensation for fishermen and coastal communities, even when the costs exceed the capacity of the shipowner, through an international fund financed by importing oil companies. Over time, this model has expanded to include ship fuel and chemicals.

Attention is now turning to the future of maritime navigation, where emerging technologies raise new questions about legal frameworks that may redefine our relationship with the seas—such as autonomous ships, green fuels, advanced propulsion systems, and the growing challenges of climate change.

In this context, the theme of World Maritime Day 2025, “Our Ocean, Our Commitment, Our Opportunity,” offers a powerful summary of a delicate equation: the ocean is a lifeline for life and trade, but its protection is a shared responsibility and an opportunity to build a more sustainable future.

In this sense, the International Maritime Organization is not merely a UN bureaucracy, but the silent guardian of ocean safety, ensuring a delicate balance between global trade and the protection of our blue planet.