Some companies and institutions strive to move their offices into towering buildings, managing their affairs from above—calling them at times “towers,” and at other times “skyscrapers.”

Yet in reality, they neither resemble true towers in their fortification, nor do they actually “scrape the sky,” for even the lowest clouds are no less than two kilometers high, while cumulonimbus clouds can reach up to eighteen kilometers. So how can these buildings truly claim to reach the clouds?

These are expressions that reveal a different kind of elevation—a psychological elevation.

One wonders: toward whom are the architects and occupants of these buildings elevating themselves? And why do they seek such heights?

Undoubtedly, it is man’s arrogance toward his fellow man, driven by pride, vanity, and a desire for superiority—no matter the cost in waste or corruption.

This brings to mind the words of Allah Almighty in Surat Ash-Shu‘ara’:

“The Thamud denied the messengers *when their brother Saleh said to them, ‘Will you not fear Allah? Indeed, I am to you a trustworthy messenger. So fear Allah and obey me.’”

The Prophet Saleh (peace be upon him) continues warning his people in the same chapter:

“And you carve from the mountains, houses with pride. So fear Allah and obey me. And do not obey the command of the transgressors—those who spread corruption on earth and do not set things right.”

It is again what Allah Almighty warns us against in Surat Al-Isra’:

“And do not walk upon the earth arrogantly. Indeed, you will never pierce the earth, nor will you reach the mountains in height. All of that—its evil is detested by your Lord.”

Returning to our modern reality—could these towering buildings reflect a hint of arrogance or corruption on earth?

The bitter truth: yes, undoubtedly so.

The phenomenon of “excess in construction” is not limited to matters of management and business. There are also individuals who aspire to live in these towering buildings—something that might seem surprising to some, considering that the traditional function of a dwelling has always been to protect against weather conditions and ensure the safety of the family. Yet, it appears that human needs and goals have shifted over time and evolved alongside successive revolutions, just as urban planning developed to address the problems of overcrowding.

Nevertheless, humanity has not yet mastered all aspects of constructing high-rise buildings. Many issues have emerged that negatively affect the environmental, urban, and social dimensions of life. Consequently, governments around the world have begun to take notice of this urban problem, enacting laws and implementing measures to mitigate the challenges associated with it.

In a paper titled “The Social Face of Homo Sapiens” published in New Scientist magazine, Stuart Fleming notes that the function of what could be defined as a “home” has undergone significant evolution. Early humans lived in caves primarily as shelters, chosen for being naturally habitable and requiring no complex construction.

In regions lacking caves, Fleming explains, simple shelters were built to meet basic human needs. Later, the hut emerged as a refuge in agricultural societies. With the rise of the Industrial Age, however, the house became a more secure and private sanctuary. Today, the very concept of “home” has become far more complex.

Fleming adds that early dwellings were temporary—such as those of nomadic communities or Australia’s Indigenous peoples, who relied on hunting and gathering for sustenance in the simplest ways. Then came seasonal houses, used for specific parts of the year, for several months or one particular season—as seen in Kenya, Tanzania, and among some Native American communities—which led to the notion of collective ownership.

He further discusses how agricultural societies introduced the idea of permanent dwellings. These communities began to settle in one place for extended periods because farming and harvesting required stability. This is evident in ancient Egyptian civilization and among the Maya tribes of Central America. Agricultural stability brought about a remarkable architectural legacy and a division of labor, as individuals began to possess distinct professions and unique homes.

With the gradual emergence of cities, the concept of permanent housing evolved from mere protection to comfort. Evidence of this shift is clear today—around 75% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, and the proportion slightly exceeds 80% in industrialized nations. As populations grow and urban expansion accelerates, humanity has lost much of its available land area, according to the United Nations.

This ongoing reduction in available land space prompted architects to turn toward vertical construction—building higher structures to create more usable space while consuming less land. However, this approach did not stop at moderate vertical expansion; it gave rise to what are now known as skyscrapers, built for both residential and commercial purposes.

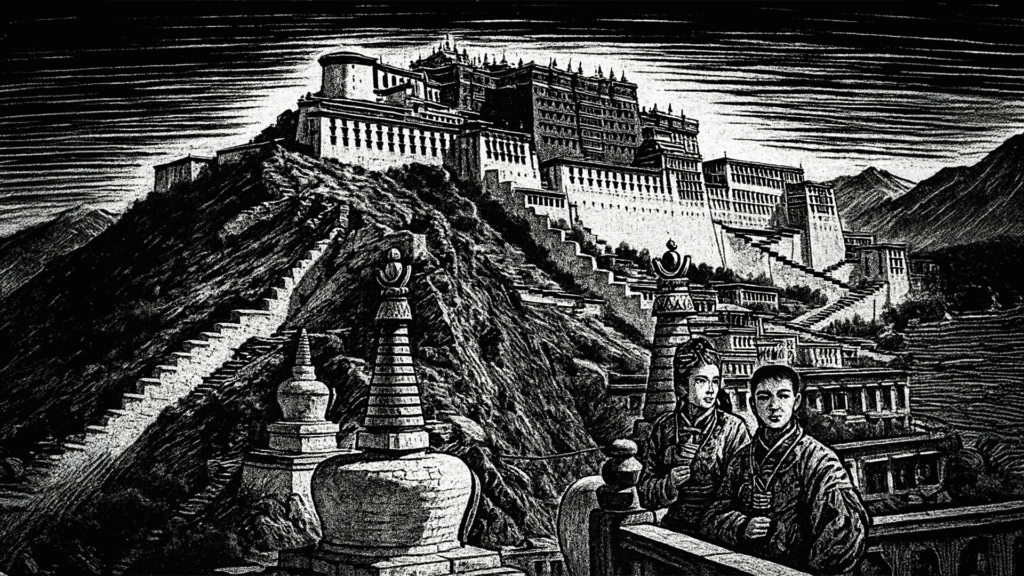

These towering buildings follow in the footsteps of ancient empires, from the Tower of Babel to the Pyramids of Giza. Historically, as David Nicholson-Cole explains in his article The First Century of Skyscrapers: A Brief History, tall structures were initially erected for religious purposes. The Great Pyramid of Khufu, built around 2500 BCE, reached a height of 145 meters. It was commissioned by King Khnum Khufu, who regarded himself as the son of the sun god Ra, a semi-divine being representing the deity on earth.

The ancient Egyptians believed in building a bridge between earth and sky—one through which the king’s soul could ascend to the heavens and, conversely, descend back to his body upon resurrection. This idea is echoed in the motivation behind constructing the Potala Palace in Tibet, which was built high on the mountains to be closer to the heavens. The Great Pyramid of Khufu remained the tallest structure in the world until the construction of Lincoln Cathedral in England in the late 11th century, which reached a height of 160 meters.

Modern skyscrapers first appeared as prominent landmarks of modernity in the urban landscapes of Chicago and New York during the 1880s.

According to Leslie Hudson in her book Chicago Skyscrapers in Old Postcards (2004), the first tall building of the modern industrial era reached 12 floors and was designed by the American architect William Le Baron Jenney. This was due to the technological boom that swept the United States during the 1880s and 1890s, which produced innovative solutions that allowed architects to construct taller buildings.

At that time, iron factories began producing alloys that were more flexible than before, making it possible for elevators to reach beyond ten floors. Thus, high-rise towers started to appear in densely populated cities such as Paris, London, Manhattan, and Hong Kong, particularly in commercial districts. This triggered a revolution in office design, enabling companies to centralize their operations in a single location—especially with the emergence of trams, subways, and railways that transported employees from their homes to unified workplaces, decades before the widespread ownership of private cars.

The French geographer Jean Gottmann observed in 1966 that since the late nineteenth century, major cities had been racing to construct tall buildings. In his paper titled Why the Skyscraper? , he explored the motives behind their construction, viewing skyscrapers as an important geographical phenomenon that reflected specific economic activities and conveyed economic and social meanings that left their mark on the urban landscape.

From this emerged the concept of the city skyline, which took on a special significance in major cities, while skyscrapers themselves became a standard architectural model.

In another paper titled The Skyscraper and the Skyline , Gottmann adds that Manhattan exemplifies this trend. He explains that New York began to lose its importance after World War II, when its port lost its economic role with the rise of aviation.

As the development of Manhattan and New York City, both densely populated, became increasingly costly, major companies began relocating to other states such as Chicago, Denver, and Los Angeles. During that period, residential buildings, hotels, and office towers exceeding 30 floors were constructed—rising like towering mountains.

However, as Gottmann notes, New York returned to the race in 1964, when the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were built over an open plaza, each comprising 110 floors and standing 410 meters tall. At that time, Chicago’s Sears Tower was the tallest building in the world at 440 meters. With the completion of the Twin Towers, New York reasserted its dominance through the power of height.

Moving to Asia, particularly China, skyscrapers have seen rapid growth in recent years. In an article titled Asia Dreams of Skyscrapers by Jason Barr, published in The New York Times, the author notes that the Ping An Finance Tower in Shenzhen, southern China, was completed in 2017 with 115 floors. Similarly, the Shanghai Tower, completed in 2015, reached 128 floors, making it the second-tallest skyscraper in the world—a symbol of the region’s drive to attract residents, tourists, and investments.

Even the Arabs, as Aaron Betsky remarks in his article “The Symbolism of Skyscrapers: The Meaning of Tall Towers Around the World,

are no longer merely “oil field diggers.” They have become global traders and investors, and most of the skyscrapers across the Arabian Peninsula now stand as symbols of wealth and power, whether privately or government-owned. They proclaim themselves as proud, soaring monuments.

A fitting example appears in Matthew Keegan’s article What Is the Most Vertical City in the World? published in The Guardian. He notes that Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, standing at 828 meters, dominates the Gulf skyline, alongside dozens of other towers under construction—including the Dubai Creek Tower, which was temporarily halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but is planned to exceed 1,000 meters in height.

However, Richard Florida, in his article The Relationship Between Skyscrapers and Great Cities published on Bloomberg, points out that many countries have begun to notice the negative impacts of high-rise buildings and have started to impose restrictions to avoid them. He adds that while some may believe that skyscrapers are modern and practical, this assumption is not always accurate. They are not always the best solution — and their drawbacks are numerous.

In some cities, these towers have hindered housing growth, road infrastructure, and commercial development due to the lack of sound urban planning, which can stifle innovation and social interaction, especially in poorly lit neighborhoods.

Florida further explains that some of the most innovative environments are found in old industrial areas, such as Chelsea and Cambridge, where medium-height buildings, open layouts, and historic character allow people and ideas to interact freely — leading to the emergence of startups and new innovations.

Thus, excessively tall buildings can negatively affect both social and economic life. A balance in height is therefore necessary — to avoid excess and to achieve the best urban and creative outcomes.

A paper published by the American Concrete Institute, titled International Concrete: Design and Construction, confirms that vertical construction comes with challenges such as social isolation, environmental pollution, and complex building systems. Without careful planning, such structures can become more dangerous to their residents and surroundings.

Although engineers have long been eager to design and build what are called skyscrapers, many have now begun criticizing them, having discovered unforeseen harms. These buildings require massive efforts to prevent vibration, consume enormous quantities of steel and concrete, and need deeper, stronger foundations to support their towering heights.

Furthermore, according to Matthew Wells in his book Skyscrapers: Structure and Design (2005), skyscrapers consume huge amounts of energy to operate air conditioning, artificial lighting, and elevators — making their carbon emissions much higher than those of medium-rise buildings.

While it’s true that skyscrapers may solve housing issues and provide office space, they also lead to the excavation of hundreds of thousands of tons of soil for deep foundations, and the release of greenhouse gases and carbon emissions, accelerating the pace of climate change.

Dan Cortese, in his article Why Did China Ban Skyscrapers? , notes that the world has begun to take into account the risks and downsides of skyscrapers, and that cities have started implementing new rules and regulations to address these concerns.

For example, in Beijing’s Central Business District, height restrictions were set at no more than 180 meters for new projects. In other parts of China, the Wuhan Greenland Center, initially planned to reach 636 meters, was reduced to 500 meters.

The decision, issued in 2018, came after construction had already begun on several towers, forcing radical redesigns. Around 70 buildings originally planned to exceed 200 meters were suspended, even after work had started — three of them were supposed to surpass 500 meters, including the Golden Finance 117 Tower in Tianjin, which has remained largely unfinished for more than a decade, and the Wuhan Greenland Center, which has remained incomplete since 2017 despite its reduced height.

Therefore, I believe that architecture and urban planning represent a continuous process of evolution throughout history, shaped jointly by technology and culture. With each new revolution — from the agricultural, to the industrial, and now the digital — the concept of buildings and homes has changed, as have human needs.

At first, stability of place was important. Then, permanence became a necessity. Later, as people pursued livelihoods in large cities, permanence lost significance, leading to overcrowding. Urban growth shifted vertically rather than horizontally, filling cities with people and tall buildings — among them, skyscrapers.

All too often, environmental and social considerations were overlooked. The world has since begun to take corrective action — imposing restrictions on location and height, and building new cities — in hopes of curbing vertical growth and returning, at least partially, to horizontal expansion.