I have personally been subjected to numerous scam attempts that fortunately did not succeed. Among them were repeated phone calls at spaced intervals from individuals speaking in a Gulf dialect that, to my Egyptian ear, sounded perfectly convincing. They falsely claimed to be calling from the bank or the police and asked for my ID details and bank account information. Honestly, the first time I was hesitant—I did not know whether it was a scam or something legitimate. But I remembered the warning bulletins issued by Qatar’s Ministry of Interior about such suspicious calls, so I did not respond to any caller.

Over time, I became skilled at recognizing such scammers from their very first sentence. I even began taking the initiative, asking the caller, “So what do you want now—my bank account number and my ID number, right?”

They would pause briefly, after which I would tell them there was no need to attempt to scam me. Sometimes I deliberately wasted their time by asking questions that eventually led me to give them false information. On one occasion, I advised the caller that unlawfully taking people’s money is a grave sin and urged him to repent. He apologized and hung up.

The imagination of fraudsters has gone so far that they now call pretending to be police officers—a tactic that several Gulf countries, including Qatar and Kuwait, have warned against. Authorities have emphasized that the police never request bank account details or ID information over the phone.

What is truly painful is that I personally know two highly educated and well-informed individuals who work in journalism, and all of their bank savings were stolen after they fell victim to a text message containing a malicious link. Each of them lost more than one hundred thousand dollars. Attempts to recover their money were unsuccessful, despite filing an official police report and repeatedly contacting the bank.

Amid this feeling of sadness, I sometimes recall a comedic YouTube video that has surpassed 57 million views, featuring a British comedian named James Veitch. He decided to play along with a scam email he received, without revealing any real personal information or sending any money, simply to test the scammers’ persistence and the remarkable absurdity of their responses.

Like many others, Veitch received a mysterious email from an unknown person named Solomon Odonkoh, promising him a profitable gold deal. He says that for any ordinary person, the natural reaction would have been to press delete and move on—but he chose to do the exact opposite and replied.

That decision turned a fleeting scam message into an experiment that lasted for years, during which he exchanged dozens of emails with online scammers, uncovering a bizarre world of inverted logic and absurd situations.

Veitch realized that the best way to derail a scammer was through comedic escalation—by playing along and pushing the conversation into pure absurdity. When the so-called Odonkoh offered him 10% of a gold shipment worth $2.5 million, Veitch responded, “What is this small amount? Let’s start with a full ton of gold.” The scammer then found himself forced to match this escalation, completely abandoning the scripted routine he was used to.

In an attempt to build an emotional connection, the scammer asked him, “What will you do with the money?” Instead of giving a reasonable answer, Veitch wrote a long message about hummus—its varieties and how to eat it with carrots. The result was a moment of total confusion that pulled the scammer out of character, ending with a strange line Veitch wrote: “Good night, you piece of gold.”

Even more amusing was that the scammer was willing to go along with any absurd condition to keep the “deal” alive. When Veitch invented a secret code based on dessert names, he received a reply from the scammer using the same terminology—one of the most satirical moments of the entire exchange.

Veitch insists that his goal was not merely humor, but wasting the scammers’ time. “Every minute they spend with me,” he said, “is a minute they can’t spend stealing a vulnerable person’s savings.” In this way, his experience became a playful form of resistance against digital fraud.

He warns against using one’s real personal email for such experiments, after his inbox was flooded with spam, and advises using a separate, disposable email address instead.

He warns against using one’s real personal email for such experiments, after his inbox was flooded with spam, and advises using a separate, disposable email address instead.

What is certain is that digital fraud is no longer a marginal phenomenon; it has become one of the fastest-growing types of crime in the world. It combines modern technological capabilities with the intelligence of organized criminal networks and targets the weakest point in the entire system: the human being.

Today, scammers exploit digital media in all its forms—from the internet and smartphone applications to trading platforms, social media, and electronic payment systems—within a complex ecosystem where technology integrates with psychological deception and social engineering techniques.

Today, scammers exploit digital media in all its forms—from the internet and smartphone applications to trading platforms, social media, and electronic payment systems—within a complex ecosystem where technology integrates with psychological deception and social engineering techniques.

Specialized international bodies define digital fraud as a set of fraudulent activities carried out through digital means with the aim of stealing victims’ money or data, or unlawfully obtaining services or financial benefits.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision at the Bank for International Settlements defines digital fraud, in a document titled Frequently Asked Questions on Climate-Related Financial Risks, as fraudulent activities conducted through digital channels—such as computer networks, smartphones, payment applications, and social media platforms—primarily targeting banking systems and customers. These activities rely on deception, misrepresentation, and data manipulation to mislead individuals or institutions into surrendering money, data, or services.

Thus, the essence of digital fraud can be said to rest on the convergence of three key elements: a clear fraudulent intent to seize money or data; a digital medium such as the internet, phone, application, or platform; and deliberate deception of the victim through identity impersonation, false information, or the use of fake websites and applications that appear legitimate.

In its 2024 Internet Crime Report, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) explains that digital fraud takes on a wide spectrum of methods. The report recorded hundreds of thousands of complaints related to email fraud, phishing, investment scams, identity impersonation, extortion, and other forms of online crime.

One of the most common methods is traditional phishing via email, SMS messages, or instant messaging applications such as WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger. In these cases, the victim receives a message that appears to come from a bank, payment platform, government agency, or major corporation, asking them, for example, to update their information, unfreeze an account, or resolve an alleged financial transaction.

The danger lies in the fact that the message contains a malicious link leading to a fake website that closely resembles the legitimate one in its logo, design, and layout. The victim then enters login credentials, bank card details, or verification codes, which are immediately captured by the scammers.

The FBI has dedicated a website titled How We Can Help You to raise awareness about this type of fraud, its various forms, and how to prevent and report it.

The FBI has dedicated a website titled How We Can Help You to raise awareness about this type of fraud, its various forms, and how to prevent and report it.

They also promote fraudulent investment offers that lure victims with high, guaranteed returns—only to disappear after collecting the funds.

They also promote fraudulent investment offers that lure victims with high, guaranteed returns—only to disappear after collecting the funds.

Another common tactic is impersonating technical support staff to convince victims that their devices are infected, then demanding payment or asking for remote access to their devices.

Another common tactic is impersonating technical support staff to convince victims that their devices are infected, then demanding payment or asking for remote access to their devices.

Scammers frequently target elderly individuals through romance scams or phone calls, exploiting their need for emotional support.

The FBI’s website How We Can Help You explains that a large portion of digital fraud occurs online through malicious links, malware-laden attachments, or messages impersonating well-known entities via email or social media. The site warns users to avoid clicking suspicious links and to verify the sender’s identity by visiting the official website directly rather than relying on links provided in messages.

The website also outlines simple yet crucial preventive measures, including not sharing personal information, being cautious of offers that promise unusually high returns, using strong and unique passwords, enabling two-factor authentication whenever possible, and verifying the source of any message before engaging with it.

If exposed to digital fraud, the FBI recommends swift and organized action by filing an online complaint with the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), contacting the nearest field office, and cooperating with relevant legal authorities such as the U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

In addition to general phishing, targeted phishing—often called spear phishing—has become increasingly common. This type of attack specifically targets companies or individuals, particularly financial officers within organizations. In such cases, scammers gather detailed information about the victim from public sources such as LinkedIn, company websites, news articles, and reports. They then send carefully crafted messages that appear to come from a CEO, business partner, or primary supplier, requesting an urgent transfer of funds to a new account under the pretext of closing a deal or correcting a financial error.

This type of fraud falls under what is known as Business Email Compromise (BEC), which the U.S. Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) identifies as one of the most financially costly crimes for businesses in terms of transferred funds. Digital fraud methods also include emails containing malicious attachments disguised as Word documents, PDFs, or compressed files. These may contain spyware or malware that installs on the victim’s device once opened, enabling attackers to log keystrokes, steal saved passwords, or gain remote control of the system.

Investment or financial fraud is another highly dangerous form of digital fraud, particularly in the context of cryptocurrencies, contracts for difference (CFDs), and margin trading. For this reason, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), through its investor education portal, warns against the growing number of fake platforms claiming to offer forex, cryptocurrency, commodities, or stock trading services without any legitimate regulatory authorization.

Scammers create professional-looking websites and applications that display live charts, user accounts, and profit-and-loss dashboards. Initially, they allow victims to make small profits that can actually be withdrawn, creating credibility and encouraging larger deposits.

Then the platform begins showing enormous fictional profits on the screen. However, when the victim attempts to withdraw funds, they face a series of obstacles, such as demands to pay taxes, clearance fees, or transfer charges. Victims are typically asked to pay these fees upfront before any funds are released. Eventually, as new fees continue to be demanded, the platform disappears entirely or the victim’s account is blocked.

Another form of trading fraud operates through what is known as managed investment accounts or managed trading accounts. In this scheme, individuals or groups on platforms such as Telegram and Instagram claim to be trading experts who generate steady returns far exceeding traditional profits. They display screenshots of accounts showing thousands of dollars or alleged testimonials from satisfied clients. Often, these testimonials are fabricated or obtained by blackmailing previous victims with promises to recover their lost funds, turning them into unwilling accomplices in the crime.

In this type of fraud, victims are asked either to transfer money directly to the scammers so they can manage the investment entirely, or to open an account in their own name on a specific platform and grant the scammers trading authority. In reality, the account is drained through deliberately losing trades or by transferring funds to wallets controlled by the scammers—after which they disappear.

Paid signal groups are also widespread. These groups provide subscribers with instant buy-and-sell recommendations for currencies or cryptocurrencies. In some cases, they manipulate asset prices by coordinating large numbers of individuals to buy at the same time, then selling once the price rises—what is commonly known as pump-and-dump schemes.

To understand an important part of this context, it is necessary to define the forex market itself. Forex is a global market for exchanging currencies between banks, financial institutions, investors, and speculators. It is the largest financial market in the world in terms of daily trading volume. According to the Bank for International Settlements’ triennial survey of foreign exchange markets, average daily turnover in the forex market exceeded $7.5 trillion in 2022 alone.

Forex operates on the principle of buying one currency against another in anticipation of future exchange rate changes that generate profit. In essence, it is a legitimate market and, in developed countries, is subject to clear regulatory frameworks and operates through licensed banks and brokerage firms.

Forex operates on the principle of buying one currency against another in anticipation of future exchange rate changes that generate profit. In essence, it is a legitimate market and, in developed countries, is subject to clear regulatory frameworks and operates through licensed banks and brokerage firms.

There is also phone-based fraud, which represents an important extension of digital fraud crimes and is known in English as “vishing,” meaning voice phishing—randomly targeting victims through phone calls.

In this pattern, the victim receives a call from a number that appears official. Sometimes scammers use caller ID spoofing technology to display a fake number that matches a bank or government agency. The scammer introduces themselves as a bank employee, police officer, prosecutor, or regulatory official, claiming there is suspicious activity on the victim’s account, an urgent financial case that must be addressed, or that their bank card has been frozen.

Under pressure and fear, the victim is asked to provide a verification code just received via text message, their bank card details, or to follow specific steps inside their banking app. In reality, the scammer is attempting to access the victim’s account or execute a transfer and uses the verification code obtained from the victim to complete the transaction.

With the advancement of generative AI technologies, reports have emerged of synthetic voices being used to imitate the voices of managers, officials, or even relatives, making it increasingly difficult to distinguish between real and fake calls.

In addition, smartphones themselves are exposed to various hacking attempts, since they combine email, banking applications, digital wallets, and two-factor authentication tools.

One of the most dangerous methods is SIM swapping, where the attacker contacts the telecommunications company while impersonating the victim and convinces an employee to issue a new SIM card under the pretext of a lost, damaged, or replaced device.

Once the new SIM is activated, the phone number comes under the attacker’s control. Verification messages from banks, email platforms, and cryptocurrency exchanges are then received by the attacker, who uses them to reset passwords and take over accounts.

Spyware applications are also widespread. They disguise themselves as free or useful programs, such as VPN apps or games. Once installed, they transmit device data, call logs, messages, and screen content to a server controlled by the attacker.

Malicious text messages containing harmful links, unsecured public Wi-Fi networks, and neglecting to lock or monitor one’s phone all create multiple entry points for hacking or planting malware on the device.

Thamnia

An investigative podcast that tells a new fraud story each season, exploring the world of scammers through an in-depth investigative journey.

Another malicious form of digital fraud is so-called “fund recovery fraud,” where victims are targeted a second time after losing money in a previous scam. The victim receives a call or message from an entity claiming to be an international legal firm specializing in recovering stolen funds, a law office, or an investigative unit affiliated with a governmental or international body.

They may provide details that appear accurate about the platform where the victim was previously defrauded, and may even send documents bearing the logos of well-known institutions. This creates the impression that the victim’s case is under review and that part of the funds has been traced—yet they claim that upfront fees are required to cover court costs, banking charges, or taxes on the recovered funds.

Driven by hope of recovering their losses, the victim pays these fees. Then additional payments are requested under new pretexts—until the fraudulent entity disappears.

Many banks and regulatory authorities warn against this pattern, emphasizing that government agencies and banks do not require victims to pay upfront fees to recover their money. Any entity that does so is highly likely to be part of a new scam.

Psychological and social studies on victims of digital fraud indicate that being scammed does not mean the victim is naïve or unintelligent. Scammers continuously refine their methods to deceive even educated and specialized individuals.

However, certain traits increase vulnerability. Among them are impulsiveness and weak self-control. Research published in journals of economic and behavioral psychology—such as a study by Annapoorna and Savitha Basri titled The Impact of Emotional Intelligence and Behavioral Biases on Mutual Fund Trading Frequency: Evidence from India —analyzed data collected from 499 mutual fund investors through self-administered questionnaires. The data were statistically examined to understand the relationship between emotional intelligence, behavioral biases, and trading behavior.

The results show that behavioral biases such as overconfidence, herd behavior, and loss aversion directly influence investor decisions. Overconfidence was found to increase trading frequency, while loss aversion was associated in some cases with reduced trading frequency.

The study concludes that the relationship between emotional intelligence and behavioral biases is more complex than previously thought. Higher emotional intelligence does not necessarily lead to more rational investment decisions and may sometimes reinforce irrational behavior patterns. The researchers recommend integrating psychological and behavioral factors into financial advisory services and investor awareness programs to help individuals understand how emotions influence their investment decisions and reduce risks associated with excessive trading.

In the context of emotional scams, social isolation and loneliness play a significant role. Studies of victims—especially older individuals—show that weakened family and social support networks, for example after the loss of a spouse, make individuals more susceptible to online relationships built on empathy and trust that gradually turn into financial exploitation.

Another factor is low digital literacy. Many people remain unaware of the differences between official and fake websites and lack basic cybersecurity knowledge, making it easier to lure them into sharing sensitive information.

Public awareness represents the first line of defense against digital fraud. In Qatar, the Qatar Central Bank and other official bodies have launched awareness campaigns warning against financial fraud and cybercrime, including messages through traditional media, social media platforms, and banking applications.

In the United Kingdom, the Take Five to Stop Fraud campaign encourages people to pause for a few seconds before sharing personal or financial information or transferring money. It provides simplified educational materials explaining phishing emails, suspicious calls, and real-life victim examples.

Banks and financial institutions also play an important role by publishing awareness pages on their websites and applications and issuing alerts when new fraud patterns emerge, such as messages reminding customers that the bank will never ask them to share passwords or verification codes via phone or email.

Estimating the global volume of money lost to digital fraud is not easy, since many cases go unreported due to victims not realizing they were scammed or feeling embarrassed to admit it.

Nevertheless, international reports paint a concerning picture. According to the U.S. Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), reported losses in the United States alone exceeded $16.6 billion in a single year, with a significant increase in cryptocurrency-related investment fraud.

Globally, Cybersecurity Ventures estimates that the annual cost of cybercrime—including digital fraud—could reach $10.5 trillion by 2025. This figure makes cybercrime one of the largest illicit transfers of wealth in modern history, encompassing direct losses, investigation and litigation costs, regulatory fines, and losses from business and service disruptions.

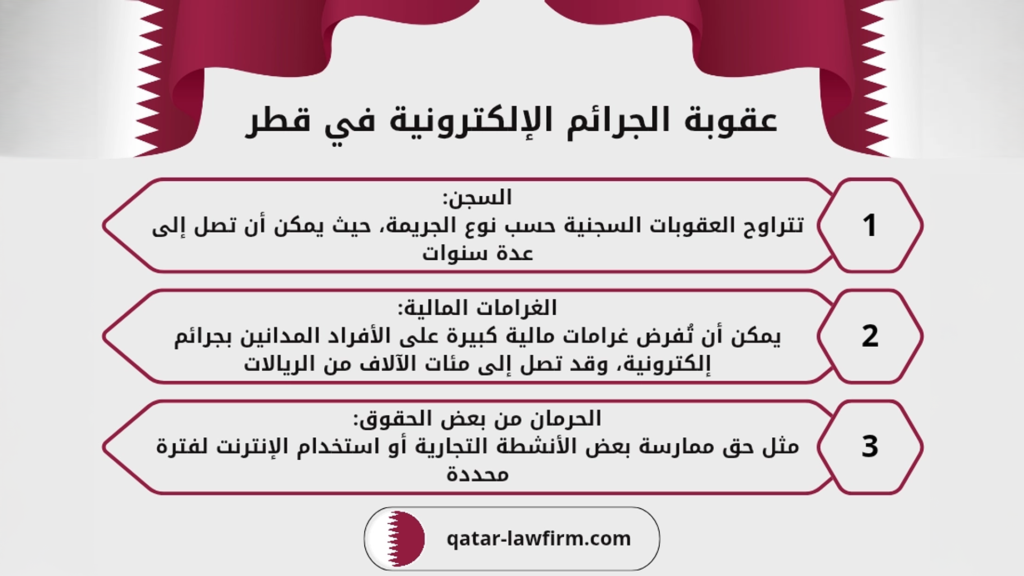

The legal framework for combating digital fraud in Qatar and the Gulf states reflects a growing awareness of the seriousness of these crimes.

In Qatar, Law No. (14) of 2014 issuing the Cybercrime Prevention Law is the primary legal reference for criminalizing unauthorized access to information systems, data manipulation, and fraud through electronic means. The law stipulates penalties including imprisonment and fines, with harsher punishments if the offense targets critical infrastructure, government systems, or financial institutions.

Among the anti-digital fraud initiatives is a broad national campaign under the slogan We Are All Aware, launched by the Qatar Central Bank in cooperation with the Ministry of Interior, the National Cyber Security Agency, and the Qatar Financial Centre Regulatory Authority to raise awareness of information security within society.

The campaign aims to strengthen information security culture among the public and empower individuals to confront cyber threats and financial fraud amid rapid technological advancement. It promotes awareness of data privacy and the dangers of fraudulent messages, calls, and malicious links in emails, text messages, and social media.

The campaign also provides practical advice to citizens on how to avoid becoming victims of such threats and encourages reporting financial cybercrimes through official hotlines, the Metrash2 application, and designated email channels.

In Saudi Arabia, the Anti-Cybercrime Law (issued by Royal Decree No. M/17 on 8 Rabi’ al-Awwal 1428H, corresponding to March 26, 2007) defines a wide range of cybercrimes and includes penalties of up to ten years’ imprisonment and fines of up to five million riyals, particularly in cases involving the unlawful acquisition of others’ funds or financial data.

In Kuwait, Law No. 63 of 2015 on Combating Information Technology Crimes criminalizes unauthorized access to systems and websites, fraud through technological means, and data theft, imposing penalties of imprisonment and fines, with the possibility of blocking certain violating websites.

In the United States, digital fraud is regulated under several federal laws. Among the most important is Section 1343 of Title 18 of the U.S. Code (18 U.S.C. §1343) , which criminalizes wire fraud—any scheme to defraud carried out via wire, radio, television, or electronic communications across state lines. Penalties may reach up to twenty years in prison, rising to thirty years and higher fines if the fraud affects a financial institution.

Additionally,the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (18 U.S.C. §1030) is one of the key legislative tools for prosecuting unauthorized access to information systems, data destruction, and data theft. It provides for both criminal penalties and, in certain cases, civil remedies.

Proving digital fraud relies on a combination of digital, financial, and testimonial evidence. Key evidentiary tools include system logs that record every login attempt to accounts, including IP addresses, device type, operating system, and approximate geographic location.

Such records often reveal that access was made from a device the victim had never used or from a country where the victim does not reside. Emails, text messages, and application chats also constitute critical evidence. Email headers can be analyzed to identify the servers through which a message passed and its true source, even if the sender attempted to conceal their identity or impersonate a legitimate entity.

Bank records and payment service provider data also play a central role in tracing the flow of funds through bank transfers or digital wallet transactions, including blockchain analysis in cryptocurrency cases.

Furthermore, forensic examination of devices by digital evidence experts can extract remnants of malware, registry files, and traces of connections to fraudulent websites, reinforcing the technical account of how the fraud occurred.

Victim and witness testimonies regarding the nature of communications and promises received are also essential in presenting a complete picture before the court. Courts often rely on technical experts to explain complex technical aspects in simplified terms to judges.

From a practical standpoint, experts advise individuals who suspect digital fraud not to delete any related messages, emails, or chats, to save screenshots of communication stages, and to request official statements from the bank or platform detailing account activity during the suspicious period. They should then promptly file an official report with the competent authorities, as rapid reporting may enable freezing funds or preventing further transfers.

Individuals are also consistently advised to activate proper two-factor authentication through trusted applications rather than relying solely on SMS messages, to use strong and unique passwords for each service, and never to share verification codes with anyone claiming to represent a bank, the police, or official authorities. A simple rule repeated in global awareness campaigns applies: Stop, think, then decide before you click, share, or transfer.

In conclusion, digital fraud today is no longer just a passing online scam; it has become a complex cross-border system that exploits rapid technological advancement and loopholes in legal frameworks, while also preying on human vulnerability in moments of need, greed, or loneliness.

Yet confronting it is not impossible. The higher the level of public awareness, the more advanced the capabilities of financial and security institutions, the stricter the legislation, and the stronger the international cooperation in sharing information and pursuing cross-border networks, the more limited scammers’ room for maneuver becomes—and the greater the reduction in losses.

The very technology they use to cause harm can also serve as a powerful tool for protection, detection, and deterrence—provided that we use it consciously and responsibly, and recognize that prevention begins with the simplest daily decisions: opening an email, answering a call, clicking a link, or deciding to enter into an investment that seems too good to be true.