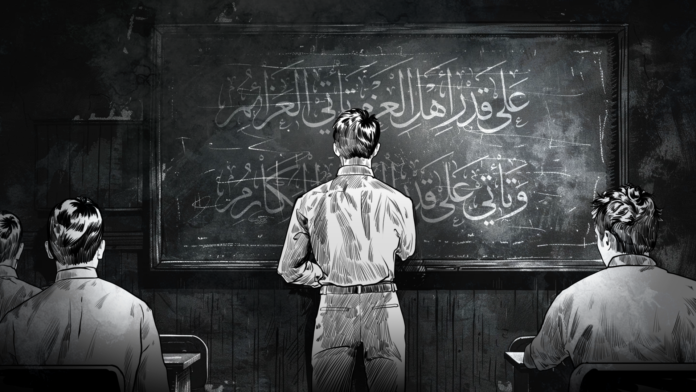

Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali took the initiative, under the commission from the caliph Ali, may God be pleased with him, to place diacritical marks on the words of the Holy Quran. This was to regulate the recitation for those newly acquainted with Islam from among the non-Arabs who made mistakes in the rules of the language. More than thirteen centuries later, the Qatari legislature enacted a law composed of fifteen articles to limit the distortion of the tongues of the Arabs and the impacts of a cultural invasion threatening their language.

In the pre-colonization era, the Arabs lived as free people who disdained subjugation. They were eloquent speakers, priding themselves on their mastery of speech just as they did on their bravery and generosity. They were aided by a quick wit and a resonant and rich language; thus, oratory thrived.

A person among us is concealed beneath his articulation by his tongue; when he speaks, he is revealed.

So, what has happened to the Arabs and the Arabic language in our time?

Someone wrote to me through social media, saying:

Since you are a linguist, I would like to consult you on an important matter to me.

I said: I am not a linguist; instead, I am a seller of words from the fields of training and media.

He said: May God increase your humility, but I passionately follow your linguistic posts, your literary writings, and your spirited nature. I am improving myself to become a poet, raised on the poetry of the first generations and the eloquence of the rhetoricians. I would like you to advise me—based on your experience—on how further to enrich myself with the anthology of the Arabs so that I may reap its benefits.

Then he complimented me, saying: I believe that your appearance, demeanour, gestures, and signals have revealed that you have understood my intent and grasped what is in my heart.

I found his words pleasing, so I answered: This matter was once the talk of gatherings, sharpening minds and arousing thoughts. It was lofty and transcendent, yet now, after the mute has spoken and the eloquent have been silenced, it no longer occupies the mind or stirs excitement. Then I saw him more If their talk baffled you the first time, there is no blame on those who spoke or disgraced.

Then, I listed who he should follow, saying: if you claim to aspire to reach the stars with your ambition and wish to follow the path of the greats, then you must turn to the works of al-Mutanabbi, the satires of al-Hutay’ah, the annals of Zuhayr, the apologies of al-Nabighah, the Hashemite verses of al-Kumayt, the rivalries between Jarir and al-Farazdaq, the innovative expressions of Kushajim, the wine poems of Abu Nuwas, the ascetic verses of Abu al-Atahiya, the comparisons of Ibn al-Mu’tazz, the praises of al-Buhturi, and the garden poems of al-Sanubari. If you do not graduate from the school of the great poets and follow in their footsteps, may God not bless your generation.

Surprisingly, he asked me, “Who are these, my teacher? Are these poets?”

Arabic Language Protection Law

Qatar has not limited itself to cultural or educational aspects supporting the Arabic language. It took a distinctive step in protecting it by issuing Law No. 7 of 2019 on the Protection of the Arabic Language, which mandates “All governmental and non-governmental authorities shall be committed to protect and support the Arabic language in all the activities and events they carry out.” It also stipulates that “State legislation shall be drafted in the Arabic language and a translation thereof in other languages may be issued, if the public interest so requires.”

The law obliges educational institutions, both public and private, to teach Arabic as an independent fundamental subject within their curricula, according to the rules and regulations set by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education.

Moreover, The law emphasizes the necessity of adhering to the Arabic language by imposing a significant financial penalty of about USD 14,000 in case of non-compliance, noting that “Without prejudice to any more severe penalty provided for in another law, whoever violates any of the provisions … of this Law shall be punished by a fine not exceeding (50,000) fifty thousand Riyals.”

The Qatari academic community has welcomed this law, as noted by Dr. Imtanan Al-Sammadi, a professor of Arabic at Qatar University, in an interview with her on Al Jazeera Net. She believes that “Arab countries need such a law to reconsider and affirm their identity, explaining that the new law includes 15 detailed clauses to ensure matters are not left vague.”

Her Excellency Ms Lolwah Al-Khater, the former official spokesperson for the Qatari Ministry of Foreign Affairs, warmly welcomed the initiative in a statement to Al-Sharq newspaper, saying, “The law for the protection of the Arabic language was not issued in vain, but came as a result of the leadership’s realization of the real need for this law.” She noted that the language is a cradle of identity and that preserving the identity cannot be achieved without maintaining the Arabic language.

She added, “The matter requires activation, understanding, and concerted efforts. This is not a matter of compulsion or obligation, but requires everyone to recognize the need for participation and that we all must work collectively to address the existing gaps.”

The Qatari writer Intisar Al-Saif believes, in an article published in the Qatari newspaper Al Raya, that legal legislation to protect the Arabic language is a necessary step, but it “will not bear fruit unless a linguistic institution concerned with the linguistic affairs in Qatar is established; such as the establishment of an Arabic Language Academy, because the linguistic situation will remain unmonitored without a legislative and executive linguistic supervisory institution that legislates and implements linguistic decisions, which are in the interest of the Arabic language.”

Confirming what Al-Saif said, we see in Algeria an example of a country that resisted cultural erosion by the French occupier. Dr. Bin Yahia Taher Naous noted in his study on the national project to generalize the use of the Arabic language in Algeria that despite Law No. 91-05, dated January 16, 1991, which includes the generalization of the use of Arabic, “Algeria still suffers from a subtle yet intense conflict between the Francophones and the Arabizers.”

Naous added, “Algeria suffers from many problems due to this duality, as since its independence on July 5, 1962, it has dedicated itself to establishing the fundamentals of the Algerian state and national identity. Its first constitution, issued in 1963, states in Article Five that Arabic is the national and official language of the state, but the ordeal of Arabization has continued since the dawn of independence, through the era of President Houari Boumediene in 1971, when Arabic began to take on an official character.”

However, the intense focus on language took another direction during Chadli Bendjedid’s presidency when the French managed to reassert their control and opposed the Arabic language law. This forced the Algerian parliament to repeal the Arabization decision “under the pretext that international circumstances do not allow it, and in other words, that Paris has placed a veto against the Arabic language in Algeria,” as Naous said.

Thus, the Algerian law has not established foundations that support the language as an institution or an academy to support the law and correct the course of the distortion that occurred to its Arabic identity.

The Need for a Law to Protect the Arabic Language

Islam Online mentions Dr Ali Al-Kubaisi, the General Director of the World Organization for the Advancement of Arabic Language, participating in a seminar titled Reading into the Law for the Protection of the Arabic Language in Qatar, hosted by Qatar’s National Library in collaboration with the Qatar Literature Initiative. The seminar discussed the realities and linguistic struggles in the State of Qatar and the challenges of globalization.

Dr Al-Kubaisi states, “Arabic is a main component of Arab identity, and understanding the interactive relationship between language and identity requires proper linguistic awareness. The absence of this awareness is the main reason for the underappreciation of the status and importance of the Arabic language.”

In an interview on the Al Arabiya channel, Dr Al-Kubaisi explained that officials and decision-makers are fully aware of the risks facing the Arabic language. “However, the majority of the people, from families to education to media and beyond, have not yet reached an awareness of the dangers threatening the language,” he said. The evidence of politicians’ awareness is “the issuance of charters in Arabic, as in the UAE, or Arabic language laws, as in Jordan and Qatar.”

Although the Arabian Peninsula is the source of the Arabic language, the Gulf countries face unique linguistic challenges. Their geographical proximity to Iran has led to a cultural clash, and Indian influences on the Gulf states from ancient times due to trade increased with the dawn of the oil era and the economic prosperity that attracted millions of workers from the Indian subcontinent. This resulted in a hybrid language that linguists call “pidgin,” which does not adhere to the rules of either language.

This hybrid or pidgin language introduces foreign vocabulary into Arabic, such as the word (SIDA) meaning ‘forward in a straight line’, the word (SAMAN) meaning ‘items’, and the word (KATSHRA) meaning ‘waste’, among other words.

As Gulf countries focus on economic development and the associated educational advancements, there has been an increased emphasis on teaching the English language, along with a notable spread of international private schools. This has made many parents feel that mastering Arabic is not a priority, mistakenly thinking that speaking the local dialect is sufficient. Furthermore, many children are raised in the care of maids who do not know Arabic, surrounding them with a foreign linguistic environment.

On the other hand, many may not know that the beginning of higher education in Egypt, for example, was in Arabic. Omar Tousson, one of the most famous princes of the Muhammad Ali family, states in his book The Crafts and Military Schools during the Era of Muhammad Ali Pasha (1935) that the medical school established in 1827 during the era of his great-grandfather was Arabic-medium. This was despite the initial instructors being French, Italian, Spanish, and German. Higher education in Egypt remained Arabized for sixty years until the British occupation imposed English-medium medical education starting in 1887.

The interest of those passionate about the Arabic language extends over a vast geographical area that has experienced successive waves of cultural invasion. This calls for a concerted cultural effort at the grassroots level and politically at the level of officials and decision-makers.

Indeed, language is a primary determinant of self and identity and an independent perspective for understanding the world.